As a so-called African-American in America, I have always felt a deep, unsettling sense of dislocation. My early years were spent on the east side of Kansas City in the 30s where my schooling at Sanford B. Lad was surrounded by children who looked like me, spoke like me and shared similar cultural backgrounds. Everything for me changed, however, when my mother remarried and we moved to the suburbs of Johnson County’s Shawnee Mission School District. The transition was not merely geographical; it was a profound shift in social dynamics, cultural exposure and personal identity.

At Ladd, my shared experiences created a bond of familiarity and mutual understanding with my peers. We celebrated our culture in ways both subtle and overt, from the rhythm and vernacular of our speech patterns, the cracking of jokes and the music we listened to that made us move, we were a community with many common ideas and practices held in unity. However, at Oak Park Elementary, I was one of the few melanated faces in a sea of Caucasian peers. The shift was jarring, forcing me to grapple with both peers and a personal crisis of identity. I felt a constant pressure to assimilate, to tone down my cultural expressions, assume stereotypes but also to conform to a different set of social norms. In a word, I was conflicted.

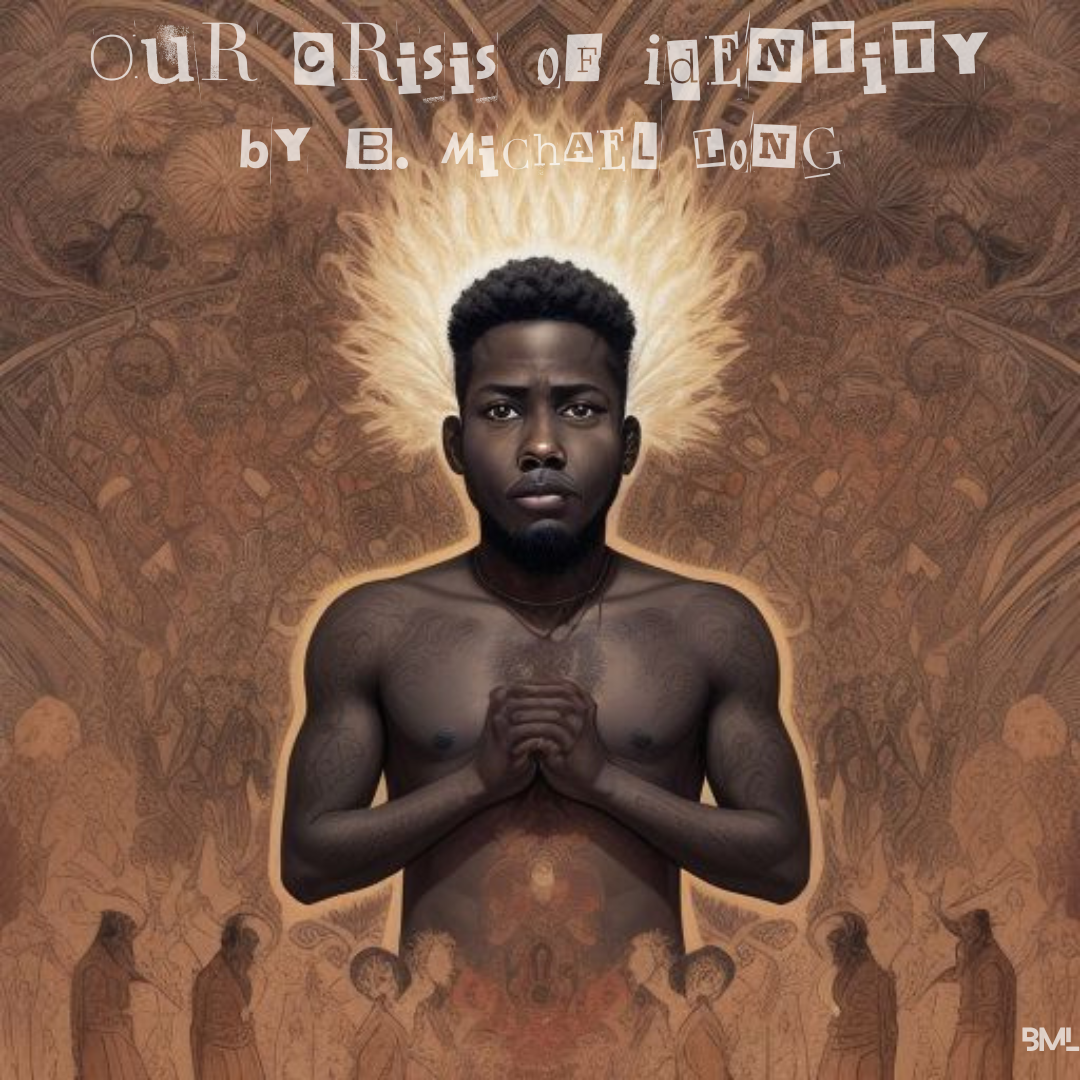

I refer to my personal anecdote to highlight a larger issue that many so-called African-Americans regularly face: the crisis of identity. This crisis stems from a lack of ancestral, cultural and historical consciousness. Being that our history as so-called African-Americans has been fragmented and distorted by centuries of enslavement, colonization, and systemic oppression, we have been intentionally disconnected from our roots which has left us struggling to define ourselves in a society that often devalues our contributions and ignores our histories. The results are glaringly evident and I dare to say that unless we reclaim our ancestral, cultural and historical identity, our future will become even more dark. This I confirm with the words of the honorable Marcus Mosiah Garvey who once powerfully stated that “a people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.” Eventually, that tree will die due to its lack of connection to source.

Frantz Fanon, in his seminal work “Black Skin, White Masks,” explores this phenomenon in depth. In his analysis of the neurotic condition of so-called Blacks, he writes, “Both the black man, slave to his inferiority and the white man, slave to his superiority, behave along neurotic lines. As a consequence, we have been led to consider their alienation with reference to psychoanalytic descriptions.” (Fanon, 1952). Fanon’s observation on the neurosis of racial dynamics underscores the psychological toll of systemic oppression, where both blacks and whites are trapped in distorted perceptions of each other and themselves. This reinforces the crisis of identity I discussed, highlighting the need for our deep cultural and historical reclamation to break free from these conditioned, destructive pathologies and patterns.

To combat this pathology and pattern, John Henrik Clarke, another profound thinker, speaks to the necessity of reclaiming our history and identity, which translates to us living unapologetically according to our ancestral, cultural and historical consciousness. He famously said, “The first and most important thing you must do is to remember who you are. You are a part of a people who have a unique history that goes back to the beginning of the human family. You must take out of your mind everything that enslavement put in and put everything back that enslavement took out.” Clarke’s words have resonated deeply with me as I have taken the challenges and pains to reflect on my own journey of self-discovery and cultural reclamation.

As I navigated my secondary and post-secondary school years, I began to understand the importance of cultural and historical consciousness. The lack of representation throughout my elementary to post-secondary educational curriculum only exacerbated my feelings of dislocation. I was taught, by design, a version of history that trivialized or entirely omitted the contributions of African-Americans, let alone Africans. This omission was a stark reminder of the systemic efforts to erase our heritage and reinforce a narrative of inferiority and subjugation to an unjust and discriminate power. If it was for my extracurricular pursuit of knowledge, I would have been lost in the sea of oblivion relative to my identity.

Yet, it was my awakening to Israelite heritage in 2001 that served as my transformative experience. With my oldest and best friend, I delved into the prophetic and historical manifestations relative to the curses of Deuteronomy 28, where we began to see the connections between our historical experiences and the ancient texts. The curses described in Deuteronomy 28 served as markings identifying the lost sheep of the house of Israel in exile. This revelation provided a profound sense of belonging and purpose for the both of us. It was as if the pieces of my fragmented identity were finally coming together. The lenses to my vision were also cleared and I began to see the world anew with a field of view that contextualized and made sense of matters past, present and future that once perplexed me.

In my experiences, I have found that it has been because of my understanding of my Israelite heritage that I’ve been offered a pathway to remedy my personal crisis of identity. It has ancestrally reconnected me to a rich culture and history that predates enslavement and colonization. It has restored within me a sense of pride and dignity that has been systematically stripped away. By embracing this heritage, I have been empowered to reclaim a positive and powerful narrative which has redefined the manufactured African-American identity I once assumed and has afforded me an ancestral, cultural and historical foundation on which to build for me and children. I now firmly believe, that though not all African-Americans are Israelites, I do, however, affirm the power in the principle of Sankofa, or repentance/teshuvah, to which I spoke of in my previous article “Repentance, Restoration and Liberation.”

In my most humble opinion, I submit that for us to address the crisis of identity among African-Americans will require a multifaceted approach. It involves an educational reform, starting at home, to ensure a more accurate and comprehensive portrayal of our history, challenging the propaganda and assault of the greatness of African history. The ACECC program, spearheaded by Dr. Kevin Bullard in concert with the Kansas City Public Schools once provided such culturally and historically enriching curriculums to our youth, dramatically demonstrating a powerful impetus for transformation of both students and testing results during the 90s and early turn of the millennium. The address will also require community engagement to celebrate and preserve our cultural traditions. And lastly, it will demand an individualized, personal commitment to self-discovery and affirmation. Only when these three dynamics are put into place, will we, as a people, start to move the needle forward into a consciousness that once typified our existence as a proud and powerful African people.

In hindsight of my journey, if I hadn’t navigated and reflected upon the complexities of transitioning from an urban to a suburban school, I would have never realized the vital importance of nurturing and maintaining a strong sense of self. My journey taught me that while environments may change, the essence of who we are must remain rooted in a deep understanding of our ancestral, cultural and historical identity. By embracing this identity, we not only honor our past but also pave the way for a future where our stories are told, our contributions recognized, our existence validated.

In the words of John Henrik Clarke, let us continue to take out everything enslavement put in us and put in everything enslavement took out of us. Only then will we fully realize the richness of our identity and the strength of our community, healing the wounds that have inflicted us and led to our crisis of identity.

by Miykael Qorbanyahu aka B. Michael Long

[email protected]

Selah.