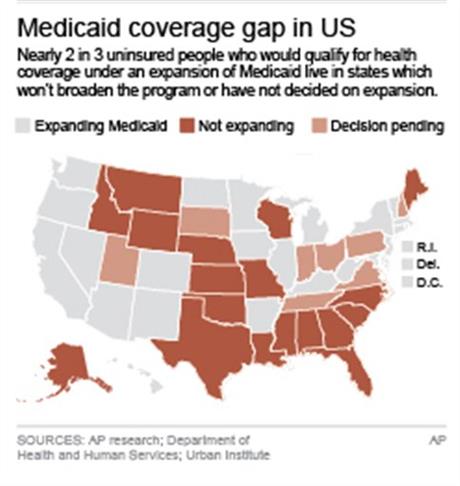

Map shows states declining to expand Medicaid or undecided; 2c x 3 inches; 96.3 mm x 76 mm;

Rick Snyder, Gene Michalski, Jeffrey Ditkoff

FILE– In this July 1, 2013 file photo, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, center, joins Beaumont Health System President and CEO Gene Michalski, left, and Dr. Jeffrey Ditkoff at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., to discuss the Healthy Michigan plan. As the GOP in Washington repeatedly calls for an Obamacare repeal, Republican governors in traditionally swing-voting states are grudgingly bowing to reality _ that the president’s health care overhaul is the law of the land and, almost certainly, here to stay. Their reluctant acceptance is based on what they call financial prudence and what appears to be political necessity. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio, File)

Prev

1 of 2

Next

DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Despite unrelenting pressure by congressional Republicans to repeal President Barack Obama’s health care overhaul, GOP governors in swing-voting states are grudgingly bowing to the reality that “Obamacare” is the law of the land and almost certainly here to stay.

The governors’ reluctant acceptance is based on what they call financial prudence and what appears to be political necessity.

“My approach is to not spend a lot of time complaining,” Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad said recently. “We’re going to do our level best to make it work as best we can.”

It’s the same view embraced by fellow Republicans John Kasich of Ohio, Susana Martinez of New Mexico, Brian Sandoval of Nevada, Rick Snyder of Michigan and Rick Scott of Florida.

It’s also in stark contrast to the approach taken by Republicans in Washington, where the GOP-led House repeatedly has voted to repeal the law. Congressional Republicans may keep at it this fall to force a budget showdown even though the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the law.

After initial gripes, these Republican governors are now trying to expand health insurance programs for lower- and moderate-income residents in exchange for billions in federal subsidies. Some governors are building and running online insurance exchanges for people to shop for insurance, instead of leaving the task to the federal government.

While all face re-election next fall in states that Democrat Obama won in both his White House races, these Republicans governors say that the 2014 elections and political calculations are not driving the health care decisions.

But a year after Democrats succeeded in casting Republicans as the party of the prosperous, the governors could blunt criticism they are ambivalent to the poor by embracing billions in federal dollars to cover millions of residents without insurance.

“At the end of the day they are making the best out of a crappy situation,” says Phil Musser, an adviser to Martinez.

Lori Lodes of the Center for American Progress, a liberal-leaning think tank that supports the law, puts it this way: “They can’t risk pursuing a partisan agenda that would turn down taxpayer dollars and deny their constituents health care.”

Some Republican governors are willing to take the chance that Democrats will cast them that way for opposing the measure. Wisconsin’s Scott Walker, who is considering a presidential run in 2016, has rejected all aspects of the law. These Republican governors find comfort in surveys that show more people in the United States disapprove of the law than approve of it.

But Republican governors who have embraced the law are making a different calculation, believing they will benefit politically as more people get insurance.

“People are seeing that they are going to have access to health care that they don’t have now and that they’ve never had, and with the support of the subsidies, the cost is going to be significantly lower,” said state Rep. Greg Wren, a Alabama Republican who’s co-chairman of the National Conference of State Legislature’s health care committee.

In Michigan, where Snyder faces an uphill re-election fight and there is disagreement in his party about the law, he has argued that receiving an estimated additional $1.4 billion in federal money to bring roughly 500,000 residents under health coverage makes economic sense.

Michigan’s Republican-controlled Senate late Tuesday passed Snyder’s Medicaid expansion proposal by two votes.

Michigan voters would be more likely to support Snyder’s re-election, based on his call for expanding Medicaid, said T.J. Bucholz, of Lansing, Mich.-based Lambert-Edwards, a public relations firm unaffiliated with Snyder that has commissioned research on the issue.

“We believe Gov. Snyder’s efforts championing Medicaid expansion have helped him,” said Bucholz, “although he still has work to do.”

Ohio’s Kasich, also with a potentially difficult re-election road, promotes expanding Medicaid as a moral issue.

Kasich advisers say agreeing to include more low- and moderate-income people in the program could soothe relations with female voters or independents angry about the budget he signed in July that included new restrictions on abortion.

“Among suburban women, it could soften his image,” said Bob Klaffky, a Kasich adviser.

Three other Republican governors have agreed to the Medicaid expansion: Jan Brewer of Arizona, Chris Christie of New Jersey and Jack Dalrymple of North Dakota. Arizona, where Brewer isn’t seeking re-election, and North Dakota are Republican-leaning states; New Jersey, where Christie is running this fall, is considered Democrat-leaning.

Martinez and Sandoval have gone the furthest toward putting the law in place. New Mexico and Nevada have Democratic-controlled legislatures that support the overhaul and growing Hispanic populations that polls show favor the law. They also face less daunting re-election challenges than others.

“These are governors from the more practically oriented part of the party,” said Joel Ario, who was the director of health exchanges during Obama’s first term.

Branstad is an example.

He spent months refusing to expand Medicaid, only to strike a deal with the Legislature for Iowa to take federal dollars in exchange for adding low-income residents to a new state-run plan and paying premiums for others to get private insurance. The compromise satisfied Democrats, by covering an additional 150,000 residents, and Branstad, by not technically expanding Medicaid.

“Just because we’re cooperating, some people may try to blame us,” Branstad said. “We have to try to make things work.”

___

Associated Press writers Bill Barrow in Atlanta, David Eggert in Lansing, Mich., and Catherine Lucey in Des Moines contributed to this report.