By KAREN MATTHEWS

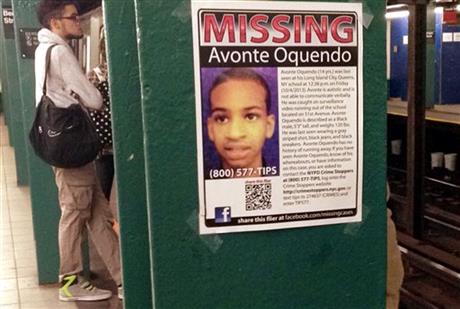

In this Oct. 21, 2013 file photo, a missing poster asking for help in finding Avonte Oquendo is displayed at a subway station in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Oquendo, 14, who is autistic, was last seen on Oct. 4 walking out of his Queens school. Avonte was in a school building that like many in the city had special-needs and general-education students together under one roof. He was outwardly indistinguishable from everybody else, leading some parents and advocates to question whether the nation’s largest school system is equipped to keep such kids safe. (AP Photo/Barbara Woike)

NEW YORK (AP) — Parents of New York City’s special-education students saw their worst fears realized four weeks ago when 14-year-old Avonte Oquendo walked out of his school and disappeared.

Avonte, who is autistic and does not speak, was in a school building that like many in the city had special-needs and general-education students together under one roof. That made him outwardly indistinguishable from everybody else, leading some parents and advocates to question whether the nation’s largest school system is equipped to keep such kids safe.

“These buildings are big, they’re overwhelming,” said Lisa Quinones-Fontanez, a mother of a 7-year-old autistic boy who publishes a blog called “Autism Wonderland.” ”The Avonte situation has really hit home because it could be any of our kids.”

Lori Podvesker, co-president of the Citywide Council on Special Education and the mother of a 10-year-old special-needs boy who, like Avonte, is nonverbal, said the city’s Department of Education must show that it is beefing up security in buildings that house vulnerable children.

“What are they doing right now to prevent this from happening again?” Podvesker asked. “We don’t know.”

About 200,000 of New York City’s 1.1 million public school students receive some kind of special-education services, ranging from weekly speech therapy sessions to more intensive programs for higher-needs students.

Under a three-year-old special-education reform initiative, city education officials are trying to keep as many students as possible in neighborhood schools rather than sending them to specialized schools. That’s in line with federal requirements that students with disabilities be educated in the least restrictive environment possible.

About 24,000 New York City students attend so-called District 75 schools that house only special-ed students, but most of those schools are in buildings shared with at least one other school. Avonte disappeared from a District 75 school in Long Island City, Queens, that shares space with a general-ed school.

While Avonte remains missing and the circumstances of his Oct. 4 disappearance are under investigation, what’s known is that a school safety officer at the front door saw Avonte and told him to go back to class. Instead he went down a hall and out a side door.

Avonte’s family has initiated legal action against the city over his disappearance.

Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said last month the school safety officer who was the last person to see Avonte did nothing wrong. Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott said this week that he has ordered his staff to examine procedures to prevent something like this from happening again.

“The special commissioner for investigations is investigating what happened, and we intend to take a serious look at his findings,” Walcott said.

Lisa Goring, vice president of family services for the advocacy group Autism Speaks, said about half of children with autism are prone to wandering. Advocates say that means the side door at Avonte’s school should have been locked on the inside and the school safety officer should have physically stopped the teen or radioed for assistance.

Podvesker, whose son attends a public school in Brooklyn, said every staff member in a building that houses students like Avonte needs to be trained to meet the needs of students with a range of special-ed diagnoses. “Are these safety guards trained in meaningful ways so that they have a basic idea of who the kids are in the building?” she asked.

Podvesker wants the public schools to improve special-ed services and security but she does not want to return to the days when children with physical or intellectual disabilities were hidden away from the general school population.

“If you say that kids like mine should not be housed in buildings with other schools you’re saying that it’s OK to segregate them,” she said. “You’re moving the needle backward if you say they should only be in buildings with like kids.”

Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said Friday that all but nine of 599 tips in the investigation are closed out, including an image snapped on a train earlier this week of a boy who looked remarkably like Avonte, but was not him.