Wikipedia

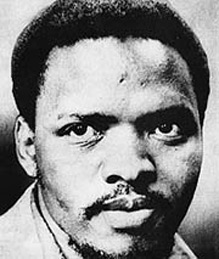

Stephen Bantu Biko (18 December 1946 – 12 September 1977)[3] was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s, until his death while in police custody.

A student leader who went on to found the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) which empowered and mobilized much of South Africa’s urban black population, he died in police custody and has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement.[4] While he was alive, his writings and activism had the goal of empowering black people. He was famous for his slogan “black is beautiful”, which he described as meaning: “man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being”.[5]

Biko was never a member of the African National Congress (ANC), but the ANC nonetheless included him in the pantheon of struggle heroes, going so far as to use his image in campaign posters in South Africa’s first non-racial elections in 1994.[6] Nelson Mandela said of Biko: “They had to kill him to prolong the life of apartheid.”[7]

Biko was born to Mzingayi Mathew and Alice ‘Mamcete’ Biko in Ginsberg Township, in what is now the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.[8] His father was a government clerk and law student. His mother did domestic work in local white homes.[9] The third of four children, Biko grew up with his older sister Bukelwa; his older brother Khaya; and his younger sister Nobandile.[10] His father gave him his name, Bantu Stephen Biko, which Biko is said to have understood to mean “a person is a person by means of other people”.[11] In 1950, when Biko was four, his father died.[12][13]

Biko was a Xhosa. In addition to Xhosa, he spoke fluent English and fairly fluent Afrikaans. As a child, he attended Brownlee Primary School and Charles Morgan Higher Primary School.[14] He was sent to Lovedale High School in 1964, a prestigious boarding school in Alice, Eastern Cape, where his older brother Khaya had previously been studying.[15] During the apartheid era, when there was no freedom of association protection for non-white South Africans, Biko was expelled from Lovedale for his political views, and his brother was arrested for his alleged association with Poqo (now known as the Azanian People’s Liberation Army).[16] After his expulsion, he attended and in 1965 graduated from St. Francis College, a Roman Catholic institution in Mariannhill, Natal.[8]

He entered the “non-European” section of the University of Natal Medical School at Wentworth, Durban, in 1966.[17]

Marriage and children

Biko married Ntsiki Mashalaba in 1970.[18] They had two children together: Nkosinathi, born in 1971, and Samora.

He also had two children with Dr Mamphela Ramphele, a prominent activist within the Black Consciousness Movement: a daughter, Lerato, born in 1974, who died of pneumonia when she was only two months old, and a son, Hlumelo, who was born in 1978, after Biko’s death.[1]

Biko also had a daughter with Lorraine Tabane, named Motlatsi, born in May 1977.[citation needed]

Steve Biko’s house in Ginsberg, Eastern Cape.

Biko was initially involved with the multiracial National Union of South African Students, but after he became convinced that Black, Indian and Coloured students needed an organization of their own, he helped found the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO), whose agenda included political self-reliance and the unification of university students in a “black consciousness.”[19] In 1968 Biko was elected its first president. SASO evolved into the influential Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). Biko was also involved with the World Student Christian Federation.

In the early 1970s, Biko became a key figure in The Durban Moment.[20] In 1972, he was expelled from the University of Natal because of his political activities[19] and he became honorary president of the Black People’s Convention. He was banned by the apartheid government in February 1973,[21] meaning that he was not allowed to speak to more than one person at a time nor to speak in public, was restricted to the King William’s Town magisterial district, and could not write publicly or speak with the media.[19] It was also forbidden to quote anything he said, including speeches or simple conversations.

When Biko was banned, his movement within the country was restricted to the Eastern Cape, where he was born. After returning there, he formed a number of grassroots organizations based on the notion of self-reliance: Zanempilo, the Zimele Trust Fund (which helped support former political prisoners and their families), Njwaxa Leather-Works Project and the Ginsberg Education Fund.

In spite of the repression of the apartheid government, Biko and the BCM played a significant role in organising the protests that culminated in the Soweto Uprising of 16 June 1976. In the aftermath of the uprising, which was met with a heavy hand by the security forces, the authorities began to target Biko further.

Death and aftermath

Stephen Bantu Biko’s grave in Ginsberg cemetery, King William’s Town

On 18 August 1977, Biko was arrested at a police roadblock under the Terrorism Act No 83 of 1967 and interrogated by the Port Elizabeth security police, including officers Harold Snyman and Gideon Nieuwoudt. The interrogation took place in Police Room 619 of the Sanlam Building in Port Elizabeth. The 22-hour interrogation included torture and beatings, sending Biko into a coma.[19] He suffered a major head injury while in police custody at the Walmer Police Station in a suburb of Port Elizabeth, and was chained to a window grille for a day.

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him into the back of a Land Rover, naked and manacled, for a 1,100-kilometre (680 mi) drive to Pretoria, where there was a prison that had hospital facilities. He was nearly dead from his injuries,[22] and died shortly after he arrived at the Pretoria prison on 12 September. Police said his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and found that he succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from massive head injuries.[19] Many saw this as strong evidence that he had been brutally beaten by his captors. Donald Woods, a journalist and editor who had been a close friend of Biko’s, exposed the truth behind Biko’s death, along with Helen Zille, who became the leader of the Democratic Alliance political party.[23][24]

Because of his high profile, news of Biko’s death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who had photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko’s life and death, writing many newspaper articles about him as well as a book titled Biko, which was later made into the film Cry Freedom.[25] Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko’s death, then–minister of police Jimmy Kruger said, “I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you… Any person who dies… I shall also be sorry if I die.”

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found that there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder, since there were no eyewitnesses.[26][27] On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated that he would not prosecute the officers.[28] On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko’s family announced that the South African government had agreed to pay the family R65,000 ($78,000) in compensation for Biko’s death.[27][29]

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission created following the end of minority rule and of apartheid reported that five former members of the South African security forces had admitted to killing Biko and applied for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.[26] On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the statute of limitations had elapsed and there was not enough evidence.[26]

Biko was buried in the Ginsberg cemetery, King William’s Town.[30][31] In 1997 the graveyard was upgraded and renamed the Steve Biko Garden of Remembrance.[30]

A year after Biko’s death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.[32]

Influences and formation of ideology

See also: Négritude

The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.

Steven Biko, White Racism and Black Consciousness

Like Frantz Fanon, Biko originally studied medicine, and, like Fanon, Biko developed an intense concern for the development of black consciousness as a solution to the existential struggles that shape existence, both as a human and as an African. Biko can thus be seen as a follower of Fanon and of Aimé Césaire, in contrast to more multi-racialist ANC leaders such as and Albert Lutuli and Nelson Mandela after his imprisonment at Robben Island, who were initially disciples of Gandhi.[33][34][35][36]

Biko saw the struggle for African consciousness as having two stages, “Psychological liberation” and “Physical liberation”. The nonviolent influence of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. upon Biko is then suspect, as Biko knew that for his struggle to give rise to physical liberation, it must exist within the political realities of the apartheid government, so Biko’s nonviolence may be seen more as a tactic than a personal conviction.[37]

Biko’s relevance today

In the present post-apartheid South Africa, Biko is revered across the political spectrum regardless of ideology. Some people see Biko’s philosophy as irrelevant after 1994, since his dream was not achieved and the ANC became the ruling party after the first democratic elections.[38] However, in 2004, he was voted 13th in the SABC3’s Great South Africans. Many present-day social movements, activists, and academics continue to stress the relevance of Biko’s black consciousness as well however. This includes a strong critique of voting by writer and political activist Andile Mngxitama who has said that if Biko were alive today, he would not be supporting any political party, would not even vote, but would be marching with the social movements against government.[39][40][41].

Tributes

Apart from Donald Woods’s book called Biko, his name has been honoured at several universities. Locally, the main Student Union buildings of the University of Cape Town are named in his honour and each year a commemorative Steve Biko lecture, open to all students, is delivered on the anniversary of his death. Internationally, the University of Manchester’s student union, the Steve Biko Building, on the Oxford road campus, is named in his honour. Ruskin College, Oxford has a Biko House student accommodation. The bar at the University of Bradford was named after Biko until it closed in 2005. Many other venues in Students Unions around the United Kingdom also bear his name. The Santa Barbara Student Housing Cooperative has a house named after Steve Biko, themed to provide a safe, respectful space for people of colour. In London, streets in both Finsbury Park[42] and Hounslow[43] are named after Biko. At the University of California, Santa Cruz, there is a dormitory named “Biko House” in the Oakes College Multicultural Theme Housing. The Instituto Cultural Steve Biko in Salvador, Brazil supports the education and pride of Black Brazilians.[44] The Pretoria Academic Hospital was renamed the Steve Biko Hospital in 2008.[45] Durban University of Technology has acknowledged Steve Biko’s contribution to South African society by naming its largest campus after him. A bronze bust of Steve Biko was unveiled in Freedom Square on that campus as a tribute. On Dec 18th, 2016 Google had a commemorative Doodle in the name of Steve Biko.[46]

References in the arts

Literature

Benjamin Zephaniah wrote a poem titled Biko The Greatness, included in Zephaniah’s 2001 collection, Too Black, Too Strong.

The Compound Arcane: Homage to Steve Biko a poem written in 1975 by Jack Hirschman, is published in The Arcanes. This poem was composed before Biko’s death, yet already the poet was inspired enough by Biko’s life to recognize him as a martyr.

In Detention by Christopher van Wyk, was published in 2007. Van Wyk, (b. 1957), also wrote We Write what we like: Celebrating Steve the same year.

Theatre, film, and television

World in Action recounted Biko’s story in a documentary called The Life and Death of Steve Biko, broadcast on ITV in the UK on 3 October 1977.[47]

A 1979 play titled The Biko Inquest, by Norman Fenton and Jon Blair, was adapted for television in 1985. Directed by Albert Finney, the adaptation originally aired in the US on HBO in 1985[48]

In 1987, Richard Attenborough directed the movie Cry Freedom, a biographical drama starring Kevin Kline as Donald Woods and Denzel Washington as Biko.

A starship name the USS Biko appears in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “A Fistful of Datas”.

Music

The most widely known musical tribute was by British musician Peter Gabriel, who released “Biko”, which became a UK hit single in 1980.[49] Gabriel’s song has subsequently been recorded by artists including Robert Wyatt, Joan Baez, Simple Minds, Manu Dibango and Paul Simon.

A Tribe Called Quest titled a song after Steve Biko on their 1993 album Midnight Marauders.

Steel Pulse dedicated the song “Biko’s Kindred Lament” to Steve Biko on the album Tribute To The Martyrs.

See also

Civil disobedience

Frances Ames

List of people subject to banning orders under apartheid

Nonviolent resistance