By GRANT SCHULTE and MARY CLARE JALONICK

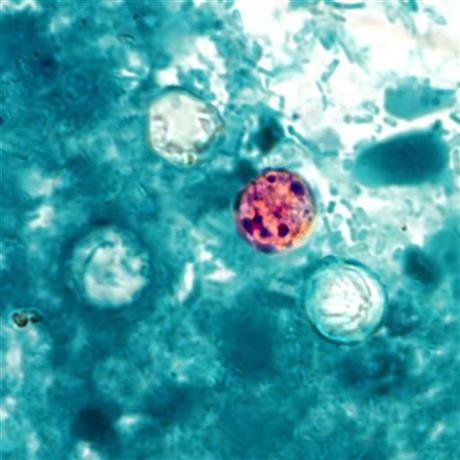

In this image provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a photomicrograph of a fresh stool sample, which had been prepared using a 10% formalin solution, and stained with modified acid-fast stain, reveals the presence of four Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts in the field of view. Iowa and Nebraska health officials said Tuesday, July 30, 2013, that a prepackaged salad mix is the source of a cyclospora outbreak that sickened more than 178 people in both states. Cyclospora is a rare parasite that causes a lengthy gastrointestinal illness. (AP Photo/Centerd for Disease Control and Prevention)

LINCOLN, Neb. (AP) — Food safety advocates say they are alarmed by a lack of information being disseminated about the spread of a nasty intestinal illness that has sickened nearly 400 people nationwide, including cases in two states that have been linked to prepackaged salad.

The outbreak of the rare parasite cyclospora has been reported in at least 15 states, and federal officials warned Wednesday it was too early to say that the threat was over.

But if you’re looking to find out exactly where it came from, you may be out of luck.

Health officials in Nebraska and Iowa say they’ve traced cases there to prepackaged salad, but they haven’t said which brand or where it was sold, explaining only that most if not all of it wasn’t grown locally.

The lack of information has fueled concern from consumers and others who argue that companies should be held accountable when outbreaks happen and that customers need the information about where outbreaks originated to make smart food choices.

“If you want the free market to work properly, then you need to let people have the information they need to make informed decisions,” said Bill Marler, a Seattle attorney who specializes in class-action food-safety lawsuits.

Heath officials in California, which provides much of the nation’s leafy green produce, said Wednesday that the state hadn’t received any reports of cyclospora cases.

“Based on the most currently available information, the leafy greens being implicated in this outbreak were not grown or processed in California,” Corey Egel, a California Department of Public Health spokesman, said in a statement to The Associated Press.

Mark Hutson, who owns a Save-Mart grocery store in Lincoln, Neb., said the lack of specific brand information threatened to hurt all providers, including the good actors.

“I think there was so little information as to what was causing the problem, that people just weren’t sure what to do,” he said. “Frankly, we would prefer to have the names out there.”

Authorities said they still hadn’t determined whether the cases of cyclospora in the different states are connected.

“It’s too early to say for sure whether it’s over, and thus too early to say there’s no risk of still getting sick,” said María-Belén Moran, a spokeswoman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Only Iowa and Nebraska officials have directly linked the outbreak in their states to a salad mix of iceberg and romaine lettuce, carrots and red cabbage. But consumers far from known outbreak areas have acknowledged it was a factor as they shopped for produce.

“I can’t say I really want to go and buy particularly any lettuce right now,” said Laura Flanagan, 35, who was shopping at a Whole Foods in Dallas with her two young children. “I’m being pretty cautious about it.”

The product was widely distributed in Iowa by wholesalers who could have supplied the bagged salad mix to all types of food establishments, including restaurants and grocery stores, said Iowa Food and Consumer Safety Bureau chief Steven Mandernach.

Mandernach said at least 80 percent of the vegetables were grown and processed outside both Iowa and Nebraska. He said officials haven’t confirmed the origins of 20 percent and may never know because victims can’t always remember what they ate.

Iowa law allows public health officials to withhold the identities of any person or business affected by an outbreak. However, business names can be released to the public if the state epidemiologist or public health director determines that disclosing the information is needed to protect public safety.

Mandernach said there is no immediate threat, so his office is not required to release information about where the product came from. He said state officials believe the affected salad already has spoiled and is no longer in the supply chain.

Nebraska public health officials said they still hadn’t traced the exact origins of the outbreaks.

“I am by no means giving all-clear, green light on the issue,” said Dr. Joseph Acierno, the state’s chief medical officer and director of public health. “We’re encouraging the medical community to stay vigilant.”

Food-safety and consumer advocates say the agencies shouldn’t withhold the information.

“It’s not clear what the policy is, and at the very least they owe it to us to explain why they come down this way,” said Sandra Eskin, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ food safety project. “I think many people wonder if this is all because of possible litigation.”

Marler said withholding the information can create general fears that damage the reputation of good actors in food production. He said consumers should be allowed to decide for themselves whether to shop and grocery stores or eat at restaurants where tainted produce was sold.

Some states also are slow to interview infected people, he said, which reduces the chances that they remember where they ate.

The Food and Drug Administration said Wednesday that it didn’t have enough information to name a possible source of the outbreak. In the past, the agencies have at times declined to ever name a source of an outbreak, referring to “Restaurant A” or using vague terms.

Caroline Smith DeWaal of the Center for Science in the Public Interest says that the decision to withhold a company’s name may not only hurt consumers but the food industry, as well. When an item is generally implicated but officials give few specifics, like with the bagged salad, people may stop buying the product altogether.

“I think consumers need more information to make good buying decisions,” she said.

Responsibility for disclosing the names of businesses involved general falls to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration because their authority crosses state lines, said Doug Farquhar, a program director with the National Conference of State Legislatures. Farquhar said most states have laws that prohibit the disclosure of businesses that are affected by a foodborne illness.

“In some cases, states go ‘rogue’ and release the names without FDA approval, in the name of public safety,” Farquhar said. “But for the most part, states prefer to let the FDA release the names and take the heat.

___

Jalonick was reporting from Washington, D.C. Associated Press writers Uriel Garcia in Dallas and Gosia Wozniacka in Fresno, Calif., contributed to this report.