By LUIS ANDRES HENAO

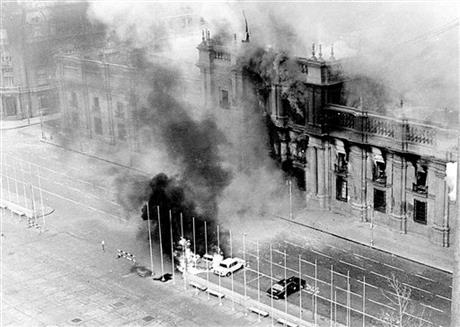

FILE – In this Sept. 11, 1973 file photo, smoke rises from La Moneda presidential palace after being bombed during a military coup led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet that overthrew President Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile. On Sept. 11, 2013, Chile marks the 40th anniversary of the coup. (AP Photo/El Mercurio, File) CHILE OUT – NO PUBLICAR EN CHILE

SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — As bombs fell and rebelling troops closed in on the national palace, socialist President Salvador Allende avoided surrender by shooting himself with an assault rifle, ending Chile’s experiment in nonviolent revolution and beginning 17 years of dictatorship.

But as the nation marks Wednesday’s 40th anniversary of the coup led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, Allende’s legacy is thriving. A socialist is poised to reclaim the presidency and a new generation, born after the return to democracy in 1990 has taken to the streets in vast numbers to demand the sort of social goals Allende promoted.

“Forty years after, he is mentioned more than ever by the young people who flood the streets asking for free, quality education,” said his daughter, Sen. Isabel Allende.

“Allende’s profile keeps on growing while Pinochet is discredited.”

Chileans have focused their anger on the costly university system installed under Pinochet, and on the vast gap between rich and poor that resulted from his free-market economic policies.

“Most of the problems affecting us today have an origin in this terrible period of our history,” said Camila Vallejo, a former student protest leader now running for Congress for the Communist Party.

Salvador Allende became the first elected Marxist leader in the Americas when he took office in 1970, though he won just 36 percent of the vote and faced a hostile Congress.

He embarked on what he called “the Chilean path to socialism,” nationalizing the copper industry that had been dominated by U.S. companies and using the money to fund land redistribution while improving health care, education and literacy.

The embrace of socialism, which included a three-week visit by Cuban leader Fidel Castro, was a Cold War nightmare for U.S. President Richard Nixon, who approved a covert campaign to aggravate the country’s economic chaos and helped provoke the military takeover.

The Sept. 11 coup initially was supported by many Chileans fed up with inflation that topped 500 percent, chronic shortages and factory takeovers. But it destroyed what they had proudly described as South America’s strongest democracy.

Pinochet shut down Congress, outlawed political parties and sent security forces to round up and kill suspected dissidents.

The list of people killed, tortured or imprisoned for political reasons during Pinochet’s regime totaled 40,018. The government estimates 3,095 of those were killed, including about 1,200 of whom no trace has ever been found.

Pinochet cut short Allende’s reforms. Chile’s schools largely had been free before Pinochet encouraged privatization and cut funding. He privatized pension and water systems, returned land to old owners, trimmed wages, slashed trade barriers and encouraged exports, building a free-market model credited for Chile’s fast growth and institutional stability.

It is his most widely praised achievement. A string of mostly left-leaning governments that followed Pinochet have left the core of that system, and even his constitution intact.

“His human rights legacy remains a complex and divisive issue for Chileans,” noted Patricio Navia, a Chilean political scientist at New York University. “But the economic model implemented under the dictatorship has been legitimized by five consecutive democratic governments led by presidents who personally opposed the Pinochet dictatorship.”

Now, however, many Chileans are starting to demand more: free education, better health care and pensions.

“This new generation is remembering that there are things that are far more important than the economy,” said Patricio Fernandez, editor of The Clinic, Chile’s most widely read weekly magazine. “It’s a return to the energy lived during Allende’s time.”

Meanwhile, the complex structures Pinochet created to protect human rights violators have corroded. About 700 military officials face trial for the forced disappearance of dissidents and about 70 have been jailed for crimes against humanity.

And even people who remained silent on previous anniversaries, including military officials, Supreme Court magistrates and right-wing lawmakers, are now apologizing for their roles during the dictatorship.

“Nothing justifies the serious, repeated and unacceptable human rights violations” committed by the dictatorship, said President Sebastian Pinera, whose center-right coalition includes many figures who worked for Pinochet.

Polls indicate that when Chileans vote for president on Nov. 17, they are overwhelmingly likely to bring back Michelle Bachelet, a Socialist Party member who left the presidency four years ago because Chilean law bans consecutive re-election. She promises to push for the most wide-ranging reforms in four decades, overhauling the dictatorship-era constitution.

Bachelet’s opponent, Evelyn Matthei, is a childhood friend whose father ran the military school where Bachelet’s own father, a general, was tortured to death for opposing the coup.

Pinochet, who died in 2006, repeatedly insisted he had saved the country from Marxism, but a poll this month found that only 18 percent of Chileans now agree. Sixty-three percent think the coup destroyed democracy, the CERC polling firm said. The survey of 1,200 people had a margin of error of plus or minus 3 percentage points.

“The right has tried to put the focus on economic reforms, the modernization of the state and the economy as Pinochet’s greatest legacy,” said Ricardo Brodsky, director of the Museum of Memory, where TV screens endlessly show the bombing of the presidential palace. “But to Chilean society today, the greatest legacy of Pinochet remains the human rights violations, the disappeared and the dead. I think this is a battle that they lost.”

__

Marianela Jarroud contributed to this report.