By RAMIT PLUSHNICK-MASTI

By RAMIT PLUSHNICK-MASTI

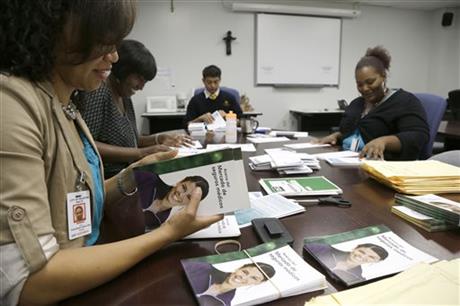

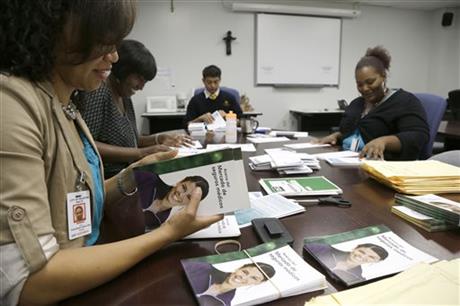

In this Oct. 24, 2013 photo temporary City Of Houston employee Lida Moreno, left, and colleagues count out Spanish language brochures for Enroll America in preparation of a door-to-door distribution in Houston. Houston is trying to reach more than 1 million people across 600 square miles who don’t have health insurance and connect them with the new federal health insurance program that began accepting applications this month. The push is happening in one of the nation’s reddest states, an example of the gap between the vitriolic political opposition to President Barack Obama’s signature initiative in some conservative bastions and the actual response to it by local officials. (AP Photo/Pat Sullivan)

In this Oct. 24, 2013 photo Yazmin Fuentes, center, works at a call center in Houston. In Houston, which paid $585 million this year to treat the uninsured in public hospitals and clinics, about 300 county employees have been trained to assist in enrollment in the new federal health insurance program. (AP Photo/Pat Sullivan)

In this Oct. 24, 2013 photo a script for handling calls about the new health insurance program rests beside a phone at a call center in Houston. The city is providing office space, laptops and cellphones for workers reaching out to the uninsured, and setting up online enrollment in city-owned buildings. The seven-person call center partly funded by the city fields questions about the program, which aims to register recipients by Dec. 15. (AP Photo/Pat Sullivan)

Prev 1 of 3Next By: RAMIT PLUSHNICK-MASTI (AP)

HOUSTONCopyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

29.7633-95.3633

HOUSTON (AP) — The scene in a city-owned building may look like a hurricane has swept through Houston: Nurses giving vaccine shots, people scurrying around with files and papers and officials leaning over computers helping bleary-eyed parents fill out forms as their children munch on free pretzels.

But this is no hurricane. Instead, it is Houston’s offensive to reach more than 1 million people across 600 square miles who don’t have health insurance and connect them with the new federal health insurance program that began accepting applications this month. The push is happening in one of the nation’s reddest states, an example of the gap between the vitriolic political opposition to President Barack Obama’s signature initiative in some conservative bastions and the actual response to it by local officials.

“This is the same strategy we use to respond to hurricanes and public health disasters,” said Stephen Williams, director of Houston’s Department of Health and Human Services, who has organized an effort to sign up as many uninsured people as possible.

Republican governors and legislatures in about two dozen states are refusing cooperation with the roll-out of the health overhaul, but some local governments are trying to fill the gap, working with nonprofit organizations, hospitals and churches leading the outreach.

After receiving only about $600,000 in federal grant money, Williams put together a 13-county coordinating group with other organizations so they could pool funds, resources and data. He also invested about $600,000 from his own budget.

“If you live in Harris County and in the city of Houston you are footing the bill for people that don’t have insurance,” Williams said. “Regardless of all the rhetoric that is going on, people have better access to care when they are insured.”

In Harris County, which paid $585 million this year to treat the uninsured in public hospitals and clinics, about 300 county employees have been trained to assist in the enrollment process. The city has provided staff, office space, laptops, air cards and cellphones. A seven-person call center partly funded by the city fields questions about the program, which aims to register recipients by Dec. 15.

Uninsured people are managing to sign up even though the process has been slowed by technical problems with the federal website. Enrollment totals are not yet available, but the collaborative has contacted more than 3,200 uninsured people since Oct. 1.

“The city has really made this priority No. 1,” said Mario Castillo, a regional leader for Enroll America, a nonprofit assisting the national effort.

Texas has the highest rate of uninsured residents in the nation — about 25 percent — and a Republican governor who has been especially hostile to the overhaul dubbed “Obamacare” by critics. In addition to withholding state funds, Gov. Rick Perry has directed the program’s trained navigators, who help recipients with the online enrollment, to receive more instruction than required under federal law.

The technical problems are just one sign of the new health system’s flaws, Perry’s spokeswoman, Lucy Nashed, said in an emailed statement. “Americans are watching Obamacare fall apart with each week that passes.”

In Florida, where Republican Gov. Rick Scott has opposed the initiative, the state ordered county health departments to ban navigators from contacting people on their property. But some local officials there are helping with the outreach to the state’s 3.5 million uninsured residents.

“We have an obligation to help them do that so they can make up their own minds,” said Mayor Kristin Jacobs in Broward County.

The city of Philadelphia is training its home visitation workers and library staff to answer questions about insurance eligibility. In Mississippi, the Health Department is providing educational information.

Nowhere, though, is the local coordination greater than in Houston — a model that Enroll America is hoping to promote elsewhere.

On a recent weekend, residents of a northern Houston neighborhood streamed into an enrollment center to get information. Navigator Susan Cockerham, who was watching a woman fill out the online application, said she has attended six similar events since the rollout began.

Orell Fitzsimmons, a labor union field director, handed out leaflets nearby.

“There are ways to get to people without having the state do it; it just takes longer,” he said.

Eunice McDonald, 62, who delivers for Meals on Wheels, said she’s had to go to the emergency room four times to treat everything from numbness in her hand to constipation in the last few years.

“I’m hoping to get health insurance,” she said, heading to a navigator. “It feels good now that I have the option.”

___

Plushnick-Masti can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/RamitMastiAP

__

Associated Press writers Kelli Kennedy in Tallahassee, Sean Murphy in Oklahoma City, Marc Levy in Harrisburg, Pa., Jeff Amy in Jackson, Miss., and Melinda Deslatte in Baton Rouge, La., contributed to this report.