By MICHELLE FAUL

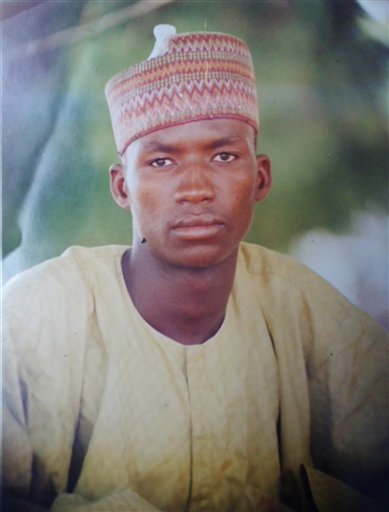

In this undated family photo provided by his sister, Hauwa Hasan Kida, Samaila Hassan Kida poses for a picture at an unspecified location. On the night of Oct. 28, 2012, security forces took Kida from the family home in Maiduguri, in an area of northern Nigeria that has been battling an Islamic insurgency. As of Aug. 28, 2013, Kida was still missing. The Civil Rights Congress of Nigeria has received ‘hundreds and hundreds, up to 3,000’ calls from people across northern Nigeria complaining that loved ones have disappeared after being arrested by the military or police in the past three years, said Shehu Sani, an activist with the organization.(AP Photo/Courtesy of Hauwa Hassan Kida)

MAIDUGURI, Nigeria (AP) — In an area of Nigeria where an Islamic insurgency has caught fire, security forces are carrying out night raids in residential neighborhoods and have arrested many people. No one knows where the detainees have wound up, whether they’re in good health or even if they’re still alive.

Distraught relatives, human rights organizations and journalists have asked the army, the police, intelligence services and government officials where the arrested people are, to no avail. No one even knows, or is saying, how many people have been detained.

Human rights monitors are deeply troubled that scores or possibly hundreds of detainees have gone missing in a country where security forces have a reputation for human rights abuses.

The Civil Rights Congress of Nigeria has received “hundreds and hundreds, up to 3,000” calls from people across northern Nigeria complaining that loved ones have disappeared after being arrested by the military or police in the past three years, said Shehu Sani, an activist with the organization.

Habiba Saadu’s two sons and her daughter were taken on Aug. 3 by soldiers who went from house to house in a night raid in Maiduguri, accusing them of participating in the uprising by Boko Haram, an armed Islamic group that has been waging a bloody war in Africa’s most populous nation for four years.

“Up to now, I have never seen my children!” Saadu said.

Visits to police stations, the army barracks, the intelligence services and local politicians gave no clue to the whereabouts of her children, Kundiri Muhammed, a 32-year-old kola nut trader, and Ka’adam Muhammed, a 29-year-old fuel seller and a daughter whom Saadu declined to name who is a high school student.

Boko Haram — which means “Western education is forbidden” — is blamed for the deaths of more than 1,700 people since 2010. The sect has attacked Christian and Muslim clerics, government health workers and security forces, school teachers and students in its quest to overturn democracy and install strict Sharia law across this nation of more than 160 million people that has a mainly Muslim north and a predominantly Christian south.

President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency on May 14 in the northeastern states of Adamawa, Borno and Yobe, giving a Joint Task Force of soldiers, police, intelligence and customs and immigration officials the right to detain people and move them from place to place, as well as the right to search without warrants.

But even under the state of emergency, Nigeria’s constitution dictates that anyone detained must have access to lawyers and family and must be brought before a magistrate within 48 hours, said lawyer Justine Ijeomah, executive director of the Human Rights, Social Development and Environmental Foundation.

“Any other detention is incommunicado and is against the law,” Ijeomah said. Even so, such disappearances are common, he said.

Asked about people disappearing, Joint Task Force spokesman Lt. Col. Sagir Musa told The Associated Press only that “if they are arrested, then they are being held.”

In its half-year report published last month, Nigeria’s federal prison service said it was holding 202 Boko Haram suspects by the end of June. Yet the military, the police and civilian vigilantes say they have arrested hundreds upon hundreds of suspects. Every day there are reports of people being detained. The disappearances of detainees began even before the state of emergency.

Journalist Hauwa Hassan Kida has spent the better part of the year searching for one of the missing. For her, the mission is a personal one.

On the night of Oct. 28, 2012, security forces took her brother, Samaila Hassan Kida, from the family home in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. Hassan and her mother got the news by telephone in Abuja, the Nigerian capital where they shared a home.

“The Joint Task Force came heavily armed in two Jeeps. They demanded everyone come out and form a queue, and when they were lined up they started beating everyone up with the rifle butts, their fists and their boots,” the reporter said, citing accounts from family members. The raiders asked for her brother by name and beat him so badly that he was unable to get into the security vehicle on his own when they ordered him inside, she said.

A family member reported Kida’s arrest to the police station opposite their home. Siblings went in search of their brother as soon as a nighttime curfew was lifted the next morning. They got leads that he had been taken by two soldiers and learned their names.

The reporter and her mother rushed to Maiduguri, where the reporter spoke with police and military officers and a leading politician but still found no trace of her brother.

“After some days, I found the soldiers that arrested him and pleaded with them, but I did not press them too much for fear they would kill him,” she said. “They are all denying they arrested him.”

Sani said his organization, based in the largest northern city of Kano in Kano state, has been receiving more phone calls in recent months despite the fact that the military had cut cellphone and Internet service to three other northeastern states and relatives had to travel to another state just to make a telephone call. Service to one of the states, Yobe, has been reinstated.

“If we go to the police, the police will say that they are not with them but may be with the military,” Sani said. “The military will say they must be with the intelligence service, the intelligence service say they don’t keep detainees — even though they do — and say they hand them over to police. So there is this cycle of confusion. The conditions in which people are being detained is very secretive.”

He had asked some families of detainees to join together in a lawsuit against government agencies and officials, including the federal attorney general, to challenge the legality of the arrests but they are afraid that doing so could put their detained loved ones in mortal danger, Sani said.

Hauwa Hassan Kida, the journalist, has returned to her work in Abuja after learning nothing about the whereabouts of her brother. Her mother refuses to join her until she finds her son.

“We still don’t know if he’s alive or dead,” the reporter said.