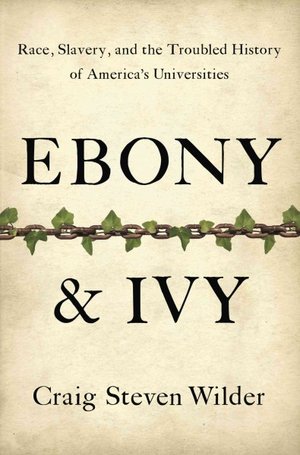

by Craig Steven Wilde

Race, Slavery, And The Troubled History Of America’s Universities

Book Summary

An African-American historian of race in America exposes the uncomfortable truths about race, slavery and the American academy, revealing that our leading universities, dependent on human bondage, became breeding grounds for the racist ideas that sustained it. Book excerpts are provided by the publisher and may contain language some find offensive.

Excerpt: Ebony & Ivy

In the daily routine of a college there was a lot of work to be done, and enslaved people often performed the most labor- intensive tasks. In the mornings, the professors and scholars needed wood for fires, water for washing, and breakfast after morning prayers in the chapel. As students ate, their rooms were cleaned, chamber pots emptied, and beds made. Multiple meals had to be produced every day in the kitchens. Ashes needed to be cleared from fireplaces and stoves, and floors needed sweeping. Clothes and shoes were cleaned and mended. Fires were lighted and maintained. Buildings wanted for repairs, and servants were impressed into small- and large-scale projects. There were countless errands for governors, professors, and students. “Titus my serv[a]nt, brought from mr. Treasurer [James] Allen (to whom I sent a Rect) Ninety Pounds Bills of Credit, being for the third Quarter, ending 17 Mar. last,” President Wadsworth recorded in the spring of 1728. Workers on more remote campuses cultivated farmlands, purchased and traded at markets, kept animals and butchered meat, and manufactured other goods on-site. In Princeton, President John Witherspoon consolidated a five-hundred acre estate, a mile from the college and with an uninterrupted view of the campus. At least one slave remained at Tusculum, where the president maintained a working farm to pursue his agricultural interests while renting the remaining lands to tenants.

Faculty and officers often testified to the difficult lives of enslaved people, but not always sympathetically. Professor Hugh Jones of William and Mary bitterly demanded that the slaves be segregated, “for these not only take up a great deal of Room and are noisy and nasty, but also have often made me and others apprehensive of the Danger of being burnt with the College thro’ their Carelessness and Drowsiness.” The Reverend Samuel Kirkland, founder of Hamilton College, encountered numerous enslaved and free black people during his early missions among the Iroquois. The Indian commissioner Sir William Johnson had slaves at his Mount Johnson estate along the Mohawk River in New York. There were also numerous black people living as residents and adoptees in Iroquoia. “I should not come here and live so much like a negro as I do,” Rev. Kirkland complained to his mentor Eleazar Wheelock; “I have lived more like a dog than a Christian minister.” Kirkland believed that his miserable living conditions were hurting the prestige of the faith among the Indians.

Access to enslaved people could be the difference between success and failure for colonial schools. Eleazar Wheelock spent his early years in Hanover supervising the building of a sawmill, gristmill, and two barns to supply the campus and to generate income. By the 1773 printing of his Narrative of the Indian Charity School — itself a fund- raising tool — he had overseen the raising of several outbuildings and was in the process of finishing a malt house. The college had eighty acres of cleared land, twenty planted with English grain and eighteen with Indian corn. Nearly fifteen tons of hay had been stacked to lessen the cost of keeping cows and oxen. His pamphlet promised additional progress: “My labourers are preparing more lands for improvement.” Nathaniel Hovey, who settled in a neighboring town in 1773, confirmed the progress over the next de cade. Captain Hovey estimated that “there have been cleared upwards of three hundred acres of land at the expence of Dartmouth College and of Moors [Indian Charity] School, that there has been a gristmill & a sawmill built and not less than two miles of road laid out and made.”

After the 1764 chartering of the College of Rhode Island, the trustees began soliciting money to prepare the grounds and build an academic hall. The active slaving towns of Providence and Newport housed a number of wealthy merchant families and high proportions of slaveholders. The prosperous slave trader Jacob Rodriguez de Rivera donated ten thousand linear feet of wood during the subscriptions for the first college building. Henry Laurens, another prominent slaver, also contributed supplies. Other residents donated the labor of their slaves. Henry Paget promised Pero, his sixty- two- year- old slave, for about a month. Another local master offered Job, an Indian slave, for more than a week.

A small army of slaves maintained the College of William and Mary. “I promise you the College is very large & well built, with gardens and out houses proportioned,” the proud parent William Gooch wrote to his brother. “The more wealthy scholars had negro boys to wait on them,” adds a historian of the college. In 1754 alone, eight students, including the brothers Charles and Edward Carter, paid fees to house their personal slaves on campus. The college also owned dozens of people.

In 1773 George Washington escorted his stepson, John “Jacky” Custis, and Jacky’s slave, Joe, to New York City. The general had vetoed the idea of placing the young man at William and Mary, fearing that the combination of planter wealth and loose discipline would only aggravate his son’s personal faults. Washington hoped that living in the North would tame Jacky’s penchant for gambling and expensive luxuries. He also wanted to control Jacky’s indecent behavior — womanizing, secret engagements, and having sex with slaves. But King’s College was not a place to learn self- discipline.

Rev. Cooper outfitted Jacky with a suite of rooms, catered to his every desire, and sent misleading reports on his progress to Mount Vernon. The teenager informed his mother that he was being treated “in a particular Light” because of his status, and that he appreciated the “distinction made between me & the other students.”

On his way to New York, Washington had a string of dinners and celebrations with governors, generals, leading merchants, and the members of elite social clubs — the strata of society that administrators needed to access. Although he had plenty of privileged boys under his charge, Cooper seized this chance to cultivate the southern aristocracy. “I dine with them (a liberty that is not allow’d any but myself),” Jacky boasted of his relationship to the faculty, and “associate & pertake of all their recreations.” An unreformed Custis left college after two years. He wasted much of his fortune, died within a de cade, and left his children to be raised by his mother and stepfather.

Reprinted from Ebony & Ivy by Craig Steven Wilder. Copyright 2013 by Craig Steven Wilder. Used by permission of Bloomsbury Press.