By ALAN FRAM and NICHOLAS K. GERANIOS

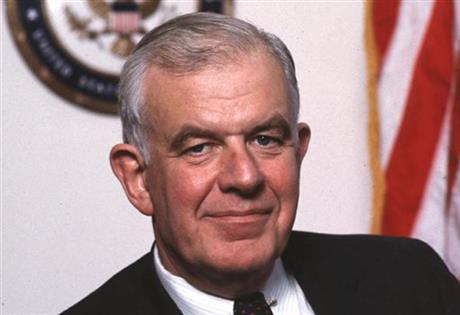

FILE – In this June 1989 file photo, former Speaker of the U.S. of Representatives Tom Foley poses in his 5th Congressional District office in Spokane, Wash. Foley has died at the age of 84, according to House Democratic aides on Friday, Oct. 18, 2013, who spoke on condition of anonymity. Foley was a Washington state lawmaker who became the first speaker since the Civil War who failed to win re-election in his home district. He was U.S. ambassador to Japan for four years during the Clinton administration. But he spent the most time in the House, serving 30 years including more than five as speaker. (AP Photo/Jeff T. Green, file)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Tom Foley, the courtly former speaker of the U.S. House who lost his seat when Republicans seized control of Congress in 1994, has died of complications from a stroke. He was 84.

His wife, Heather, said the former speaker had suffered the stroke last December and was hospitalized in May with pneumonia. He returned home after a week and had been on hospice care there ever since, she said.

Foley also served as U.S. ambassador to Japan for four years in the Clinton administration.

He served 30 years in the U.S. House, including more than five years as speaker.

The Democrat, who had never served a single day in the minority, was ousted by a smooth young Spokane lawyer, Republican George Nethercutt, who won by 4,000 votes in the mostly rural, heavily Republican district in eastern Washington state.

Foley wasn’t the victim of scandal or charges of gross incompetence. Instead, his ability as speaker to bring home federal benefits was a point Nethercutt used against him, accusing Foley of pork-barrel politics.

The public was restless that year, and the mood was dark and angry, Foley recalled later. The electorate turned on many of the Democrats it had installed in a landslide just two years earlier, dumping six congressmen in the Democrat-favored Washington state.

He was replaced as speaker by his nemesis, Georgia Republican Rep. Newt Gingrich, who later called Washington state the “ground zero” of the sweep that gave Republicans their first control of the House in 40 years. Foley, it turned out, was their prize casualty.

In a 2004 Associated Press interview, Foley said, after Senate Democratic Leader Tom Daschle of South Dakota lost his seat, that the same factors hurt them both: Voters did not appreciate the value of service as party leader, and rural voters were turning against Democrats.

“We need to examine how we are responding to this division … particularly the sense in some rural areas that the Democratic Party is not a party that respects faith or family or has respect for values. I think that’s wrong, but it’s a dangerous perception if it develops as it has,” he told the AP.

Republicans kept Foley’s old seat, even in 2006 when the national tide swung back and Democrats retook a majority in the House, and in 2008 when Barack Obama was elected president. As a party “superdelegate,” Foley had remained uncommitted during Obama’s presidential primary battle with Hillary Clinton but eventually endorsed Obama in June 2008.

House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., called Foley “a quintessential champion of the common good” who “inspired a sense of purpose and civility that reflects the best of our democracy.”

She added, “Speaker Foley’s unrivaled ability to build consensus and find common ground earned him genuine respect on both sides of the aisle.”

In a statement, House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, praised Foley.

“Forthright and warmhearted, Tom Foley endeared himself not only to the wheat farmers back home but also colleagues on both sides of the aisle,” Boehner said. “That had a lot to do with his solid sense of fairness, which remains a model for any speaker or representative.”

Foley loved the classics and art, hobnobbing with presidents, and the steady rise to power in Congress and diplomacy. But he also loved riding horseback in parades and getting his boots dirty in the rolling hills of the Palouse country that his pioneer forebears helped settle.

The Democratic giant studied at the feet of the state’s two legendary senators, Henry M. Jackson and Warren G. Magnuson. “Scoop” Jackson was his mentor and urged his former aide to run for the House in 1964, which turned out to be the Johnson landslide year for the Democrats.

Foley worked with leadership to get plum committee assignments and always seemed to be in the right place at the right time. Retirement, new seniority rules, election losses and leadership battles lifted Foley into the Agriculture Committee chairmanship by age 44. At the time, he was the youngest chairman in a century. He eventually left that post, which he later called his favorite leadership position, to become Democratic whip, the caucus’ third ranking post.

Similar good fortune elevated him to majority leader, and the downfall of Jim Wright of Texas lifted him to the speaker’s chair, where he served from June 1989 until 1995.

“I wish I could say it was merit and hard work, but I think so much of what happens in a political career is the result of circumstances that are favorable and opportunities that come about,” Foley told the AP in 2003.

He said his proudest achievements were farm bills, hunger programs, civil liberties, environmental legislation and civil rights bills. Helping individual constituents also was satisfying, he said. Even though his views were often considerably to the left of his mostly Republican constituents, he said he tried to stay in touch.

Dan Evans, a Republican former governor and senator, was among Foley’s many fans. “He was an unusually civil politician in an increasingly uncivil arena,” Evans once said.

After leaving Congress, Foley could have retired on his $124,000 pension and his investment wealth, but he went on to have two more careers — diplomacy and the law.

He joined a blue chip law firm in Washington, D.C., by one account earning $400,000, plus fees he earned serving on corporate boards. Foley and his wife, his unpaid political adviser and staff aide, had built their dream home in the capital in 1992.

In 1997, he took a pay cut to take one of the most prestigious assignments in diplomacy, ambassador to Japan. A longtime Japan scholar, Foley had been a frequent visitor to that nation, in part to promote the farm products his district produces.

“Diplomacy is not, frankly, very different” from the deal-making, consensus and common courtesy that a successful politician needs, he said.

In “Honor in the House,” the biography he co-wrote with his longtime press secretary, Jeff Biggs, Foley recounted with affection his deep roots in the district, going back to pioneer stock on both sides of the family.

His father, Ralph, was a beloved judge for decades and a school classmate of Bing Crosby’s. Ralph Foley’s father, Cornelius, brought the family to Spokane in 1907 with the Great Northern Railroad. Tom Foley’s maternal grandparents homesteaded in Lincoln County. His mother, Helen, was a teacher.

Foley attended Gonzaga Preparatory School and Gonzaga University in Spokane, working summers as a camp counselor, pharmacy delivery boy, highway crewman and aluminum company laborer. He graduated from the University of Washington Law School and worked as a prosecutor, assistant state attorney general, and as counsel for Jackson’s Senate Interior Committee for three years.

Then came the long House career.

Foley told the AP he instinctively knew in 1994 that his days were finally numbered. He said he thought about retiring that year, but talked himself into running one last time after the Senate leader retired.

For Foley, there was a deja vu quality about that election. Like Nethercutt, Foley had been a young Spokane attorney in 1964 when he ousted a longtime incumbent, the affable Republican Walt Horan, after 22 years in Congress.