By ELLEN KNICKMEYER

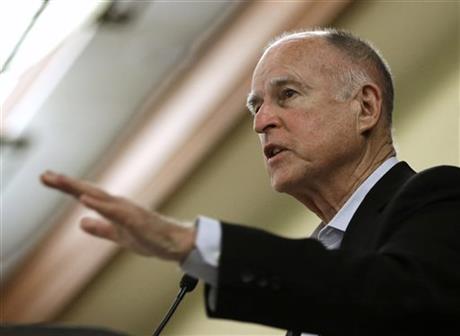

California’s top oil and gas regulators repeatedly warned Gov. Jerry Brown’s senior aides in 2011 that the governor’s orders to override key safeguards in granting oil industry permits would violate state and federal laws protecting the state’s groundwater from contamination, one of the former officials has testified.

Brown fired the regulators on Nov. 3, 2011, one day after what the fired official says was a final order from the governor to bypass safety provisions of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act in granting permits to oil companies for oilfield injection wells. Brown later boasted publicly that the dismissals led to a speed-up of oilfield permitting.

Brown’s spokesman, Evan Westrup, said Thursday that the allegations, contained in a newly filed court declaration by Derek Chernow, Brown’s fired acting director of the state Department of Conservation, were “baseless.”

This year, however, the state acknowledged that hundreds of the oilfield operations approved after the firings are now polluting the state’s federally protected underground supplies of water for drinking and irrigation.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has now given the state until 2017 to resolve what state officials conceded were more than 2,000 permits the state improperly gave oil companies to inject oilfield production fluid and waste into protected water aquifers. An earlier AP analysis of the state permits found more than 40 percent of those were granted in the four years since Brown took office.

Chernow’s declaration, obtained by the Associated Press, was contained in an Aug. 21 court filing in a lawsuit brought by a group of Central Valley farmers who allege that oil production approved by Brown’s administration has contaminated their water wells. The lawsuit also cites at least $750,000 in contributions that oil companies made within months of the firings to what was then Brown’s campaign for a state tax increase.

Chernow’s statement describes for the first time the alleged back story of the controversial permit approvals. He declined comment. Elena Miller, who was fired as the state’s oil and gas supervisor the same day as Chernow, did not respond to requests for comment.

Over the years, Brown openly boasted that he dismissed the two regulators to speed up the granting of oilfield permits in the nation’s third biggest oil producing state. His actions appeared at odds with Brown’s image as a leading proponent of renewable energy and reduced fossil fuel consumption who recently met with Pope Francis on climate change.

Westrup, Brown’s aide, said Thursday that a current campaign by Brown to as much as halve consumption of climate-changing fossil fuels in the state, and the oil industry’s fight against Brown’s climate-change campaign, shows “where the administration stands and what it’s fighting for.”

“The expectation — clearly communicated — was and always has been full compliance with the Safe Drinking Water Act,” Westrup said.

Regarding the financial and public support that the oil industry lent Brown’s 2012 campaign for a state tax increase after Brown fired the two state regulators, Westrup said, “the governor’s focus is doing what’s best for California, and that’s what informs his decisions.”

The firings occurred as the governor was scrambling to drum up energy sources, jobs and business and to win support for the ultimately successful statewide vote on tax increases to tackle budget woes.

Today, with the state in an historic four-year drought and a state of emergency declared by Brown, protecting the adequacy and purity of water supplies for farms and cities is a paramount priority.

In the declaration in the farmers’ case now, Chernow said he and Miller were under intense pressure from the oil industry as well as the Brown administration to relax permitting standards for injection wells that oil companies use to pump production fluid and waste underground.

Chernow testified he was in the office of John Laird, Brown’s secretary of Natural Resources, in early October 2011 when Laird took a call from Brown. Hanging up, Laird said, Brown had relayed just receiving a call from former Gov. Gray Davis, then acting as legal counsel for Occidental Petroleum, the country’s fourth-biggest oil Company.

Brown said Davis and Occidental had demanded Brown fire Chernow and Miller over what Occidental complained was then the slow pace of issuing drilling permits, according to Chernow.

Davis declined comment Thursday.

A few weeks later, on Nov. 2, 2011, Chernow and Miller received a call from Brown’s energy adviser, Cliff Rechtschaffen, who urged the two oil-and-gas regulators to “immediately fast-track” approval of new oilfield permits, according to Chernow’s filing.

Miller replied that what Brown aides and the oil industry were pressing for “violated the Safe Drinking Water Act, and that the EPA agreed” with that conclusion, Chernow said. In response, according to Chernow, Rechtschaffen told them “this was an order from Governor Brown, and must be obeyed.”

Chernow and Miller were fired the following day.

Memos sent to Department of Conservation staff the next month —which were obtained through state public records laws by lawyers for the farmers — allegedly detail some ways state oilfield regulators were told they could now bypass some federally mandated environmental reviews and approve permits.

Robert Stern, former general counsel of the state’s ethics agency and the architect of a 1970s state political reform act, said there was nothing illegal about Brown receiving the oil industry contributions for his tax campaign unless they were explicitly in return for firing the oil regulators.

The state, under increasing pressure from the EPA, this year and last ordered the shutdown of 23 improperly permitted oilfield wells posing the most immediate threat to nearby water wells.

Current officials in the Department of Conservation said they believe the actual number of flawed permits granted under Brown is lower than the 46 percent the state records show, but they have not provided alternate figures.

The state improperly issued permits, they said, because of misunderstandings and poor record-keeping, rather than willful decisions by Brown’s administration.

The safeguards at issue in the alleged permitting dispute were a “very fundamental” part of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act’s protections against oilfield contamination, said David Albright, manager of the EPA’s California groundwater office, this week.

California “has a huge amount of work to do” to bring its regulation of oilfield injection wells into compliance with federal law, said Jared Blumenfeld, the regional EPA administrator in California. Blumenfeld cited a “sea change” over the past year in state compliance efforts, however.

Executives of Occidental and Aera Energy at the time thanked Brown for his “involvement” in the oilfield permitting process, as Occidental CEO Steven Chazren noted in a January 2012 call with financial analysts, two months after top regulators were fired.

That month, Occidental became the first major oil company to come out in support of the Brown’s tax measure and donated the first of $500,000 to Brown’s campaign for the tax referendum. A month later, Aera donated $250,000.

Margita Thompson, a spokeswoman at what is now the independent California spin-off of Occidental, California Resources Council, said that all the farmers’ allegations were “wholly without merit.” Cindy Pollard, spokeswoman for Aera, said the company often donates to revenue-raising state campaigns. “Aera’s contributions were not quid pro quo,” she said.