By KIMBERLY HEFLING

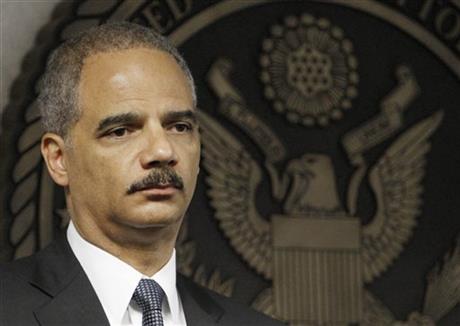

FILE – In this July 16, 2010 file photo, Attorney General Eric Holder takes part in news conference in Miami. The Obama administration is issuing new recommendations Wednesday Jan. 8, 2014 on classroom discipline that seek to end the apparent disparities in how students of different races are punished for violating school rules. Holder said the problem often stems from well intentioned “zero-tolerance” policies that too often inject the criminal justice system into the resolution of problems. (AP Photo/Alan Diaz, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Obama administration is urging schools to abandon overly zealous discipline policies that civil rights advocates have long said lead to a school-to-prison pipeline that discriminates against minority students.

The wide-ranging series of guidelines issued Wednesday in essence tells schools that they must adhere to the principle of fairness and equity in student discipline or face strong action if they don’t. The American Civil Liberties Union called the recommendations “ground-breaking.”

“A routine school disciplinary infraction should land a student in the principal’s office, not in a police precinct,” Attorney General Eric Holder said.

Holder said the problem often stems from well intentioned “zero-tolerance” policies that too often inject the criminal justice system into the resolution of problems. Zero-tolerance policies, a tool that became popular in the 1990s, often spell out uniform and swift punishment for offenses such as truancy, smoking or carrying a weapon. Violators can lose classroom time or become saddled with a criminal record.

Police have become a more common presence in American schools since the shootings at Columbine High School in 1999.

The administration said research suggests the racial disparities in how students are disciplined are not explained by more frequent or more serious misbehavior by students of color.

“In our investigations, we have found cases where African-American students were disciplined more harshly and more frequently because of their race than similarly situated white students,” the Justice and Education departments said in a letter to school districts. “In short, racial discrimination in school discipline is a real problem.”

Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of the School Superintendents Association, acknowledged that students of color were being suspended and expelled in disproportionate numbers.

In American schools, black students without disabilities were more than three times as likely as whites to be expelled or suspended, according to government civil rights data collection from 2011-2012. Although black students made up 15 percent of students in the data collection, they made up more than a third of students suspended once, 44 percent of those suspended more than once and more than a third of students expelled.

More than half of students involved in school-related arrests or referred to law enforcement were Hispanic or black, according to the data.

Domenech said his organization will work to educate members about the recommendations. “Superintendents recognize that out-of-school suspension is outdated and not in line with 21st-century education,” he said.

But, Domenech said, federal funding for programs that address school discipline issues has been scarce and some districts may struggle with the guidelines.

The recommendations encourage schools to ensure that all school personnel are trained in classroom management, conflict resolution and approaches to de-escalate classroom disruptions.

Among the other recommendations:

—Ensure that school personnel understand that they are responsible for administering routine student discipline instead of security or police officers.

—Draw clear distinctions about the responsibilities of school security personnel.

—Provide opportunities for school security officers to develop relationships with students and parents.

The government advises schools to establish procedures on how to distinguish between disciplinary infractions appropriately handled by school officials compared with major threats to school safety. And, it encourages schools to collect and monitor data that security or police officers take to ensure nondiscrimination.

The recommendations are nonbinding.

Already, in March of last year, the Justice Department spearheaded a settlement with the Meridian, Miss., school district to end discriminatory disciplinary practices. The black students in the district were facing harsher punishment than whites for similar misbehavior.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan has acknowledged the challenge is finding the balancing act to keep school safe and orderly. But, he said that, “we need to keep students in class where they can learn.”Associated Press writer Pete Yost contributed to this report