By MICHAEL BALSAMO

For months, police trying to solve a Long Island robbery spree had little more to go on than grainy surveillance footage of a man in a hoodie and black ski mask holding up one gas station or convenience store after another.

That was until the gunman made off with a stack of bills that investigators had secretly embedded with a GPS tracking device.

Within days, a suspect accused of pulling off nearly a dozen heists — including one in which a clerk was killed — was behind bars, and officers were crediting technology that has become commonplace over the past five years or so.

“Those tools are part of our arsenal,” Nassau County Police Chief Steven Skrynecki said after the arrest this summer, adding that GPS is now used “as a matter of course in our investigations.”

But the tiny satellite-connected devices — embedded by the manufacturer or slipped by police into stacks of cash, pill bottles or other commonly stolen items — are raising questions from legal experts over what they see as the potential for abuse by law enforcement authorities. They wonder whether some of these cases will stand up in court.

In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court took up the police practice of planting GPS trackers on suspects’ vehicles to monitor their movements, and it set certain constitutional boundaries on their use. It stopped short of saying a warrant is always required.

But that narrow ruling didn’t specifically address the embedding of GPS devices pre-emptively in objects that are apt to be stolen. Nor did it address how long police can engage in tracking or how they can use that information.

That has left judges with little guidance.

“This is the latest chapter in the challenge to the Fourth Amendment by new technology,” said George Washington University constitutional law professor Jonathan Turley. “There is always a concern technology can outstrip existing constitutional law. Now it’s up to the courts to decide when police departments can use this technology to facilitate an arrest and prosecution.”

So far, there have been few constitutional challenges, in part because the technology is new, but also because some defendants have pleaded guilty.

Legal experts said the courts have generally held that when people steal something containing a tracking device, police are within their rights to go after them. For decades, police have been catching car thieves through LoJack radio-tracking devices.

But civil libertarians said a legal issue could arise if police deliberately leave the tracker on for an extended amount of time to find out, for example, what other crimes the suspect might be mixed up in.

“As a baseline, I don’t think people should be tracked with GPS without a warrant,” said Jay Stanley, a policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union. “If somebody steals an object and the police don’t arrest them for six months and just collect information about how they’re living their life, that could be problematic.”

Also, legal experts worry that innocent people could get in trouble for unwittingly possessing something implanted with a GPS device.

“Just because Jim steals the money, maybe the one wad that had the GPS was one he gave to pay off a loan, or he borrowed a friend’s car and left that one there,” said New York lawyer Amy Marion.

In a case on appeal in Buffalo, a bank robbery defendant who police say was caught with a GPS-tagged bag of money is challenging his conviction, though not on constitutional grounds. He contends the cash was not enough to convict him.

The use of GPS highlights what some experts bemoan as the fast-shrinking zone of privacy nowadays, when security cameras are seemingly on every block, wireless devices broadcast our locations and tollbooths electronically record our travels.

“Not only are we living in a fishbowl society, the government can now track us in real time in the fishbowl,” Turley said.

GPS is the 21st-century version of the exploding dye pack that bank tellers slip into the bag of money during a holdup. The pack blows up outside the bank, staining the robber and the cash.

When someone walks out the door with a GPS tracker, a silent activation signal is sent to police. Officers can then use an online map, updated every few seconds, to pinpoint the object’s location,

The use of GPS has expanded as the devices have gotten smaller. Trackers as thin as a pencil can be hidden in wads of about two dozen bills.

They are also slipped into “bait bottles” of pills to thwart drugstore thieves. The bottles are typically kept behind the counter and are handed over by the pharmacist if a robber demands drugs.

The maker of the painkiller OxyContin says such bottles used in 33 states have helped police make nearly 160 arrests.

In Redlands, California, a criminal attached a “skimmer” — a device for stealing people’s credit card numbers — to a gas pump. Police put GPS on the skimmer, then caught the suspect after he collected the equipment.

In other cases, officers have made arrests through “virtual stakeouts” after leaving trackers in copper wire, bicycles and laptops.

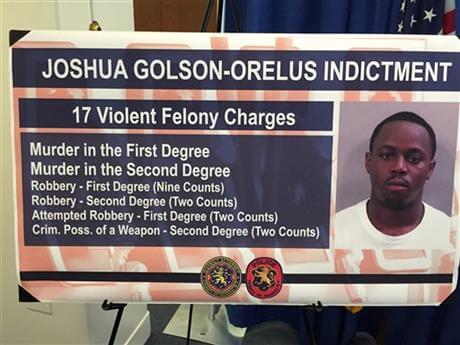

In Long Island’s Nassau County, 23-year-old Joshua Golson-Orelus has been charged with murder and armed robbery in the series of heists. His attorney declined to comment about the role of GPS.

“We’re in a different world than we were 30 years ago,” said James Carver, president of the police union in Nassau County, “and we need to take advantage of what’s being offered out there.”