By REBECCA SANTANA and MUNIR AHMED

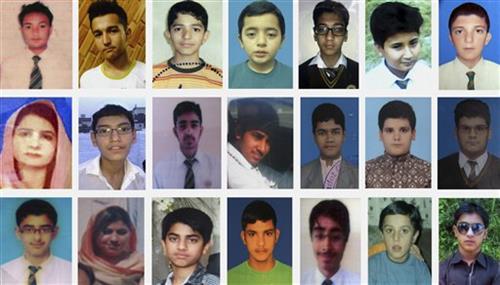

As they buried their children Wednesday, the families spoke of their dreams. One boy had just gotten high marks on his midterm and hoped to become a pilot. A 13-year-old wanted to become a doctor. Another kid just loved playing video games with his cousins.

At cemeteries across the Pakistani city of Peshawar, families lowered the rough wooden coffins of young boys and their teachers into the cold ground and gathered under funeral tents or at home, trying to comprehend the militant attack a day earlier on a school that killed 148 people, almost all of them young students.

The Pakistani government and military vowed a stepped up campaign aimed at rooting out militant strongholds in the country’s tribal regions along the border with Afghanistan. In a sign of how deeply the attack shook Pakistan, the head of the military flew to Kabul and sought help from the Afghan government — which with Islamabad has long had a tense relationship — against militant commanders behind the attack, a Pakistani military official told The Associated Press, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to the press..

In downtown Peshawar, the family of Shyer Khan, a 14-year-old student killed on Tuesday, gathered to comfort his father, who was too overwhelmed by grief to talk.

Shyer’s older brother, Muneeb, was in the auditorium when gunmen burst through the doors Tuesday morning, took the stage and began shooting randomly. He fell to the floor and pretended to be dead.

“There was so much bloodshed,” Muneeb said softly. “I closed my eyes and lay on the floor for an hour.”

When the militants moved on to other parts of the school, he escaped through a door. His younger brother, however, was in a nearby classroom and was killed when the militants burst in and opened fire. At the gathering in the Khans’ home, his family spoke of how Shyer was a fan of video games like “Call of Duty” and teasing his sisters.

In Tuesday’s attack on the military-run school, the militants first set fire to a car in a nearby neighborhood, likely as a diversion, residents said. Seven gunmen then scaled the school’s brick fence. They headed into the building and up the stairs to the auditorium, where many students were gathered.

They broke open the doors, took to the stage and started indiscriminately firing, said military spokesman Maj. Gen. Asim Bajwa.

The military took media on a tour of the site on Wednesday.

Blood splattered the stairs outside the auditorium. Inside, the scene was even worse.

Large pools of blood smeared the floors. A ninth-grader’s notebook lay torn on the stage, next to a psychology textbook and some broken glasses. A large sign outside listing membership in various school committees appeared untouched while another wall was riddled by bullets. Bajwa said the military recovered about 100 bodies from the auditorium.

In the administration building, where Bajwa said the final gunbattle between security forces and the militants took place, the walls were covered with bullet and shrapnel marks. Streaks of blood and soot marked where some of the attackers blew themselves up. The floor was covered with shards of glass, pieces of clothing, pottery and torn flowers. Outside was a small pile of body parts.

The Pakistani Taliban, which has waged an insurrection against the government for a decade, claimed responsibility. The group says it was seeking revenge for a military assault launched in June in North Waziristan.

Pakistan has often been accused by Afghanistan of tolerating or protecting Afghan Taliban or other militants on its soil as a way to pursue its interests in its neighbor, while only trying to crack down on militants who attack Pakistani targets, like the Pakistani Taliban.

But in the wake of Tuesday’s bloodshed, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif used is strongest language yet vowing there will be no discrimination between “good or bad Taliban.”

“We will continue this war until even a single terrorist is not left on our soil,” he said.

Sharif lifted a ban on the death penalty for terrorist crimes, which has been in place since 2008. He and military and civilian law enforcement officials also met to discuss the legal system’s “inadequacies in punishing terrorists.” Terrorism cases in Pakistan rarely end with convictions because of threats to judges and witnesses and poor investigations.

In Kabul, Pakistani army chief Raheel Sharif met in Kabul with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and with Afghan and U.S. military officials and shared intelligence about the attack, the military said.

A Pakistani military official with knowledge of the meeting said Pakistan asked Afghanistan to take action against Mullah Fazlullah, the head of the Pakistani Taliban, who Pakistan has long said is hiding in Afghanistan’s rugged border region. Call intercepts and recordings were given to Afghan authorities to show Fazlullah’s involvement from Afghanistan soil, the official said.

The two governments vowed to work together against militants — a sign of a slight easing of tensions since Ghani took office several months ago.

Across Pakistan, stunned people held candlelight vigils in solidarity with the Peshawar victims.

In Peshawar, families were simply trying to cope with their grief. The army-run school was well respected in the city, and many parents sent their children there in hopes of a good education.

“My son was a brilliant student,” Haji Dost Muhammad said. He spoke of the gold medal his son Asad received a few weeks ago for his midterm scores. The boy was shot in the back and killed, the family learned. He “wanted to be a pilot,” his father said, “but his soul flew from his body before he could fly a plane.”

Aurangzeb Khan sat with photos of his son Hassan on the floor in front of him in the family living room, he described how he rushed to the school Tuesday looking for any word on his children. One of his elder sons searched hospitals to see if Hassan was wounded but found his body instead.

Another father on Wednesday buried his 13-year-old son, Muhammad Haris, in the Peshawar suburbs. The boy dreamed of becoming a doctor, said his father, Ghulam ud Din, a retired military man.

He pointed toward the fresh grave. “But today I buried both the body of my son and his dream here in this graveyard.”

___

Associated Press writers Riaz Khan in Peshawar, Ishtiaq Mahsud in Dera Ismail Khan, Asif Shahzad in Islamabad and Tim Sullivan in New Delhi contributed to this report.