BY MARK MORRIS

The Kansas City Star

A notorious figure from Kansas City’s civil rights history has a critical appointment this week.

Raymond L. Bledsoe, a 51-year-old white man sentenced 30 years ago for the racially motivated 1980 killing of jazz musician Steve Harvey, who was black, faces a parole hearing Wednesday at his federal prison in Minnesota.

Despite a life sentence for violating Harvey’s civil rights to use a public park, and despite at least three previous parole denials, Bledsoe stands a reasonable chance of getting out of prison this time.

That prospect troubles friends and family of Harvey, a young saxophonist who was an emerging talent on the U.S. jazz scene. They are concerned that Bledsoe, who was 19 when he beat Harvey to death with a baseball bat, never has taken public responsibility for the killing since his federal conviction in 1983.

The murder also has remained vivid for lawyers who worked on the case more than a quarter century ago. U.S. District Judge Scott O. Wright, who tried the federal case, said Harvey’s killing shocked Kansas City and brought swift calls for justice.

The case remains one of the most memorable of his judicial career, Wright said. And though he expressed no opinion as to whether the U.S. Parole Commission should release Bledsoe, Wright recalled Bledsoe’s unsettling reaction to the sentence he received in May 1983.

“He was a strange duck,” Wright said. “I gave him a life sentence and he didn’t show any emotion. It was like nothing had happened.”

The evening of Nov. 4, 1980, Bledsoe and two friends left a party to “harass homosexuals” at Penn Valley Park, then a popular meeting spot for gay men, according to federal court records.

At a park restroom, Bledsoe encountered a white man and struck him in the head with a piece of wood. But he allowed the white man to escape.

In an adjacent restroom, Bledsoe found Harvey and pursued him into the middle of an adjacent sports field.

“(Bledsoe) stood over Harvey and, using an overhand swing, repeatedly struck him on the top of his head,” court records stated. “The blows crushed Harvey’s skull.”

Afterward, Bledsoe told others that he had killed an African-American homosexual man, though he said it in much cruder terms.

After Harvey’s death, the next shock came in August 1981 when a Jackson County jury acquitted Bledsoe of first-degree murder. Jurors, lawyers said later, likely did not find Bledsoe’s two friends credible. Each had cut plea deals for their testimony against Bledsoe.

Two efforts then began in earnest to bring Bledsoe back to court.

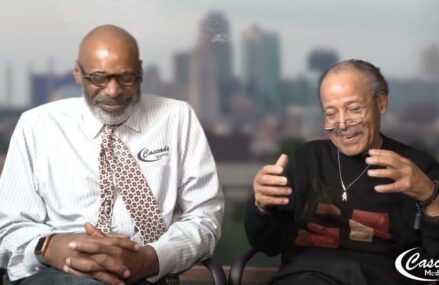

On the public front, Alvin Sykes, a friend of the slain musician, organized the Steve Harvey Justice Campaign to keep the issue before the community and pressure prosecutors to file civil rights charges. Sykes delivered petitions containing 6,000 signatures to the Justice Department calling for action.

Behind the scenes, federal prosecutors and investigators were at work building a better case. In December 1981, Bledsoe’s embittered former girlfriend told authorities that he had admitted killing Harvey, leading investigators to search for other such witnesses.

And a young FBI agent searched records at hospitals near Penn Valley Park and identified the white man whom Bledsoe had beaten before moving on to Harvey. The fact that Bledsoe had allowed a white man to escape while killing a black victim would prove crucial.

After a weeklong trial, a jury convicted Bledsoe of violating Harvey’s civil rights.

Appealing the conviction, Bledsoe’s defense lawyers argued unsuccessfully that the evidence “established, if anything, that he beat … Harvey to death because he believed him to be a homosexual and not because he was black.”

Such an attack would not have violated the civil rights law of the time, though it would now.

Under rules in place in May 1983, once Bledsoe serves 30 years in prison, he is eligible for “mandatory parole.”

To keep him locked up, the parole authorities must identify reasons not to let him out, a commission spokeswoman said recently. Those reasons could include serious and frequent violations of prison rules or a “reasonable probability that he will commit any federal state or local crime.”

How Bledsoe has performed in prison isn’t completely clear, but some hints are available. He is being held in a low-security facility in Sandstone, Minn.

Court records show that a 1999 parole commission review found that he qualified for a 2007 parole hearing because of his “superior program achievement” as an inmate.

Commissioners noted he had spent 16 years in prison industries “with excellent work reports,” had completed forklift operation courses and finished three vocational training courses.

In 1997, however, Bledsoe was found “culpable” for a serious assault on another inmate. Other reports showed that he was guilty of four less-serious infractions of prison rules.

Sykes believes that is ample evidence to keep Bledsoe in prison. He said he recently filed a statement with the parole commission arguing that Bledsoe should remain in prison for his full sentence.

He noted that the commission recently denied parole for a former Black Panther sentenced to life for the 1973 murder of a California park ranger. As for Bledsoe’s potential for further crime, Sykes said he is concerned for his own safety should Bledsoe be released.

“I’m high profile and I’m out here,” Sykes said. “(Harvey’s murder) wasn’t an isolated incident. He consistently engaged in this activity based on race.”

Harvey’s daughter, Hope Hyder, said she also has asked the parole commission to keep Bledsoe in prison. Hyder, who was 6 when her father died, said Bledsoe should accept responsibility for her father’s death.

“I’m not walking around with anger towards him,” Hyder said. “But given what he chose to do and what our society provides, the best outcome was reached. It’s entirely appropriate for him to stay there.”

Should Bledsoe be released, he would emerge into a world that is profoundly different from the one he left and at odds with his early history of racial hatred and homophobia, experts said.

A black man is serving his second term as president. And a short drive up Interstate 35 would take Bledsoe to Iowa, where same-sex marriage is legal.

Rita Flynn, who manages the TurnAround prisoner re-entry program for Catholic Charities, said she would recommend that Bledsoe’s parole officer find a good mentor to help him cope with the cultural and technological changes that have occurred since his incarceration.

TurnAround has about 70 mentors who help released prisoners manage the stress that comes after being released from a substantial prison sentence.

“Thirty years is a long time,” Flynn said.

Read more here: http://www.kansascity.com/2013/04/22/4197138/1980-killing-causes-new-anguish.html#storylink=cpy