By JOHN ROGERS

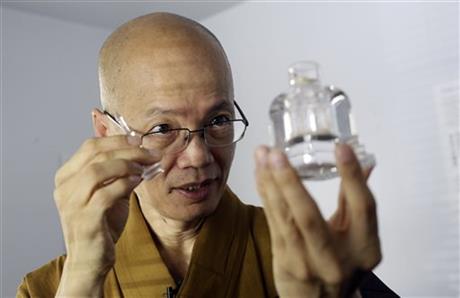

In this Sept. 18, 2013, photo, Dharma Master YongHua displays a bottle containing aromatic shariras, part of the temple collection of Buddhist relics at the Lu Mountain Temple in Rosemead, Calif. The temple has become a repository for the colorful crystals and a tooth and a hair that are believed to have come from the body of Buddha himself. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

ROSEMEAD, Calif. (AP) — Although he’d been a practicing Buddhist for 20 years, until 10 months ago Dharma Master YongHua hadn’t even seen so much as one of the sacred relics known as shariras that are so important to his faith.

So it came as quite a surprise to the modest, soft-spoken monk when he learned he was becoming the caretaker of more than 10,000 of them.

YongHua’s modest Lu Mountain Temple became a repository for the thousands of colorful crystals, two teeth and a single hair that are believed to have come from the body of the Buddha himself. A congregant offered up the collection that he’d painstakingly gathered for years.

The relics are said to be capable of producing miracles for people who go near them. And although Buddhists, like members of other religious groups, say that has to be taken on faith, even the skeptical are starting to believe miracles are happening since the shariras arrived.

“In the beginning, I didn’t really know what to think,” said Vickie Sprout, who meditates at the temple.

Following YongHua’s advice to keep an open mind, she and others noticed, they said, after six months of meditation in the presence of the shariras, that their efforts were leading to a more relaxed, blissful state.

Looking back, YongHua said, it was no small miracle that the relics even made it to Lu Mountain Temple.

Located on the corner of a hillside residential street, the temple is easily mistaken by average passers-by for what it once was: a modest, 1950s-era, cookie-cutter tract home in an aging bedroom community east of Los Angeles. A glance down the hill offers a smog-shrouded view of hundreds of other homes, all looking the same.

The handful of monks who live there like it that way. They rise at 3:30 a.m. each day and, inside the ornate temple that outsiders never see, they spend much of their days in quiet meditation.

“When we’re cultivating Buddhist teachings we’re kind of hidden,” said Master Xian-Jie. “We don’t want a lot of people around.”

Since the shariras’ arrival, there have been quite a few people around.

Hundreds from around the country arrived earlier this year when the monks put the relics on display.

They crowded up to the altar, around a statute of the Buddha and elsewhere for an up-close view of thousands of colorful crystals, some believed to have come from the heart and other body parts of the Buddha himself when he was cremated nearly 3,000 years ago.

Other crystals are believed to have come from his family members and disciples, said YongHua, as the bespectacled, brown-robed monk showed them off again to visitors last month.

“To us, shariras are very important because if we see them we think we see the Buddha himself, even though the Buddha passed away a very long time ago,” said Thu Nguyen, a 70-year-old retired day-care worker who traveled from San Jose with a dozen fellow Buddhists to see them.

The last time she was in the presence of shariras, she said, was more than 10 years ago at a temple in the Chinese city of Shanghai.

Although such relics can be found at other Buddhist temples around the country, such a large collection is unusual, said Sonya Lee, a University of Southern California professor and expert on Buddhist art and culture.

Tam Huyhn, a retired groundskeeper and recently ordained monk who donated them, said he embraced Buddhism as a means of survival after the former South Vietnamese army officer was sent to a prison camp in the 1970s following his country’s civil war. After his release, he emigrated to the U.S. in the 1990s.

He began collecting the relics a few years ago after finding they’d healed the pain he felt in his legs. During a visit to Lu Mountain Temple last year, he said he had a vision that they should be where more people could see them. That left YongHua with a dilemma.

Since their arrival, the frugal monks, who survive mainly on donations, have had to increase security and gird themselves for increased numbers of visitors. YongHua said he hopes to eventually create a stupa, or gathering place, for them like those found in India and Asia, though he knows fundraising isn’t a monk’s forte.

Still, he said, the monks are honored that for whatever reason, the Buddha smiled on them.

“And we feel compelled to share the connection with everyone,” he said.