By BEN FOX

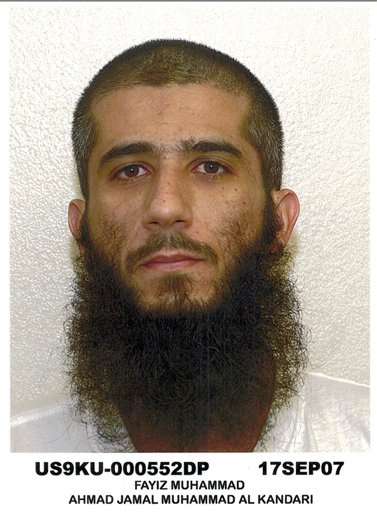

In this Sept. 17, 2007 photo released on Aug. 13, 2013 by defense lawyer U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Barry Wingard, detainee Faez al-Kandari, 36, is shown in Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base. Faez al-Kandari is a Kuwaiti who has been held for more than 11 years at the Guantanamo Bay prison. The Pentagon says the roughly 50 men in the indefinite detention category are held under international laws of war until the “end of hostilities,” whenever that may be. As a group, they are one of the chief hurdles to President Barack Obama’s attempts to close the detention center on the U.S. base in Cuba. (AP Photo/Courtesy of defense lawyer U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Barry Wingard)

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba (AP) — As the U.S. renews its effort to close the Guantanamo Bay prison, it will soon begin reconsidering the fate of prisoners such as Mohammed al-Shimrani.

The 38-year-old Saudi is in a special category among the 166 prisoners at Guantanamo — one of nearly 50 men who a government task force decided were too dangerous to release but who can’t be prosecuted, in some cases, because proceedings could reveal sensitive information. While the rest of the prisoners have been cleared for eventual release, transfer or prosecution, al-Shimrani and the others can only guess at their fate.

“The allegations against my client are no more serious than many, many Saudis who have been sent home,” New York-based attorney Martha Rayner said of al-Shimrani. “It just baffles me.”

The Pentagon says the men in the indefinite detention category are held under international laws of war until the “end of hostilities,” whenever that may be. As a group, they are one of the chief hurdles to President Barack Obama’s attempts to close the detention center on the U.S. base in Cuba.

For the most part, they have been accused of being al-Qaida and Taliban fighters, couriers and recruiters. After more than a decade, their lawyers say it’s time to let them go.

Their lawyers recently began receiving notifications that intelligence officials from “various U.S. government agencies” would begin reviewing the detention of their clients to determine whether it was still necessary to hold them. A Defense Department spokesman, Army Lt. Col. Joseph Todd Breasseale, said the date for the first hearing hasn’t been set.

Details of how the panels will be conducted, whether, for example, lawyers for the men will be allowed to be present or can only appear by videoconference, have not been disclosed.

Rayner, a professor at Fordham University School of Law in New York, said she is hopeful because her client has family to receive him back in Saudi Arabia, and a government capable of providing any security assurances the U.S. might need.

“I am going into this with an open mind,” she said.

Many who have long pushed for the closure of the prison say the U.S. needs to act fast because the legal premise for their indefinite detention will evaporate when the U.S. pulls its troops out of Afghanistan in 2014, effectively ending the war that prompted the opening of Guantanamo in January 2002.

“Our credibility is strained to begin with, but whatever is left is going to be sorely harmed if we continue to detain people after the rationale has expired,” said Morris “Moe” Davis, a retired Air Force colonel who served two years as the chief prosecutor for the Guantanamo military commissions.

The men in the indefinite detention category include three Saudis, al-Shimrani among them, who were held back as dozens of fellow citizens were sent to a rehabilitation program in their country. It also includes two Kuwaitis, Faez al-Kandari and Fawzi al-Odah, who have been accused of being part of the terrorist group and are being held even though Kuwait has built a rehabilitation center for them that sits idle. Also on the list are several Afghans, who officials have said are possible candidates for a prisoner swap with the Taliban involving an American POW, Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl of Idaho.

Al-Shimrani, who worked as a teacher in Saudi Arabia, was accused of training with al-Qaida and fighting against the Northern Alliance and possibly being a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden. Rayner argues there is no longer any legal or security justification for holding him.

Most of the government’s court filings on him are sealed. In general, however, the reason the government often opted not to prosecute men on the indefinite list was because their capture involved aid from foreign governments that did not want their assistance disclosed or because U.S. authorities used technological capabilities they did not want to publicize, said Davis, the former chief prosecutor. “It wasn’t that there wasn’t good evidence; it was an inability to use that evidence,” he said.

Air Force Lt. Col. Barry Wingard, a military lawyer for al-Kandari, who is accused of producing al-Qaida propaganda, insists there is a lack of evidence. “If the government could successfully prosecute these guys they would,” he said. “But they can’t and they won’t.”

The U.S. began using Guantanamo to hold “enemy combatants” in the chaotic early days of the war in Afghanistan. Al-Shimrani, captured in Pakistan after fleeing Afghanistan, was among the first arrivals, a core group who it was thought would yield valuable intelligence about al-Qaida. He was eventually interrogated at least 88 times, according to court documents. The prison, meanwhile, grew to a peak of about 680, with Afghans and Saudis the two largest groups by nationality.

Amid global pressure, Obama vowed to close the prison upon taking office but was thwarted by Congress, which enacted legislation that prohibited the transfer of prisoners to the U.S. and made it harder to send them abroad.

An administration task force divided the prisoners into three, somewhat fluid, categories in January 2010: those who should be considered for trial; those who should be transferred overseas or released; and those who should be held indefinitely under the laws of war. At the time, there were 48 on the indefinite list but two have since died. The number may also grow since some of the two dozen designated for prosecution currently can’t be charged because Congress has prevented them from being tried in civilian courts and an appeals court ruling found they couldn’t be charged by military commission.

Meanwhile, the government is fitfully moving ahead with military trials for some of the men whose cases were deemed fit for prosecution. Defense Department officials are returning to Guantanamo Bay on Sunday for a weeklong pretrial hearing for five prisoners facing charges that include murder and terrorism for planning and aiding the Sept. 11 attacks. The trial is at least a year away. The exact number of prisoners who can be prosecuted will depend on pending appeals of court decisions and other factors.

The U.S. has also made some progress on the nearly 90 prisoners approved for transfer or release, recently naming a new State Department envoy to lead the effort and approving long-stalled transfers for two Algerians.

That leaves the fate of the indefinites up to the intelligence officials on Periodic Review Boards. In the early years of his captivity, al-Shimrani was disdainful of a military panel weighing whether he should be held as an enemy combatant, sending a defiant note that said “judge me the way you like.”

Some of that defiance may have worn off. Rayner describes him as “troubled” by his open-ended incarceration.

“You know indefiniteness is quite cruel, it really leaves someone psychologically at sea,” she said.